| Date interviewed | 6th September 2017 |

| Date newsletter posted | 26th January 2018 |

| Farmer | Piers Garnett |

| Farm | Mayfield Farm – Doringkop |

| Mill | Gledhow |

| Total farm size | 300 hectares |

| Area under cane | 206 hectares |

| Natural bush | 80 hectares |

| Distance from coast | 35 kms |

| Cutting cycle | 16-17 months |

| Best yield | 160 tonnes/hectare |

| Av Yield | 94 tonnes/hectare |

| Best RV | 11,45 |

| Av RV | 10,58 |

| Varieties | Too many to mention – 17 to be exact! (Seedcane operation) |

| Other crops | Macadamias – about 10 hectares

Essential Oil crops – 8 hectares PLUS 4 about to be planted |

As unassuming and humble as the man is in real life, in my mind, Piers Garnett was a formidable, focused and private man whom I would never have the privilege of interviewing. My very first SugarBytes interview, with Basil Oellerman – Piers’ next door neighbour – cemented my perception because I actually met Piers that day and afterwards Basil agreed that he would probably never consent to an interview. So, once again, I am humbled and very grateful that another top farmer graciously welcomed me into his home, giving me most of his day and knowledge. I know you’ll learn so much from this visit. In fact, I know that life-long neighbours are learning about each other through SugarBytes: Piers sheepishly told me that he even learnt things about Basil, a man he has lived next door to most of his life, in the article we published on him.

HISTORY

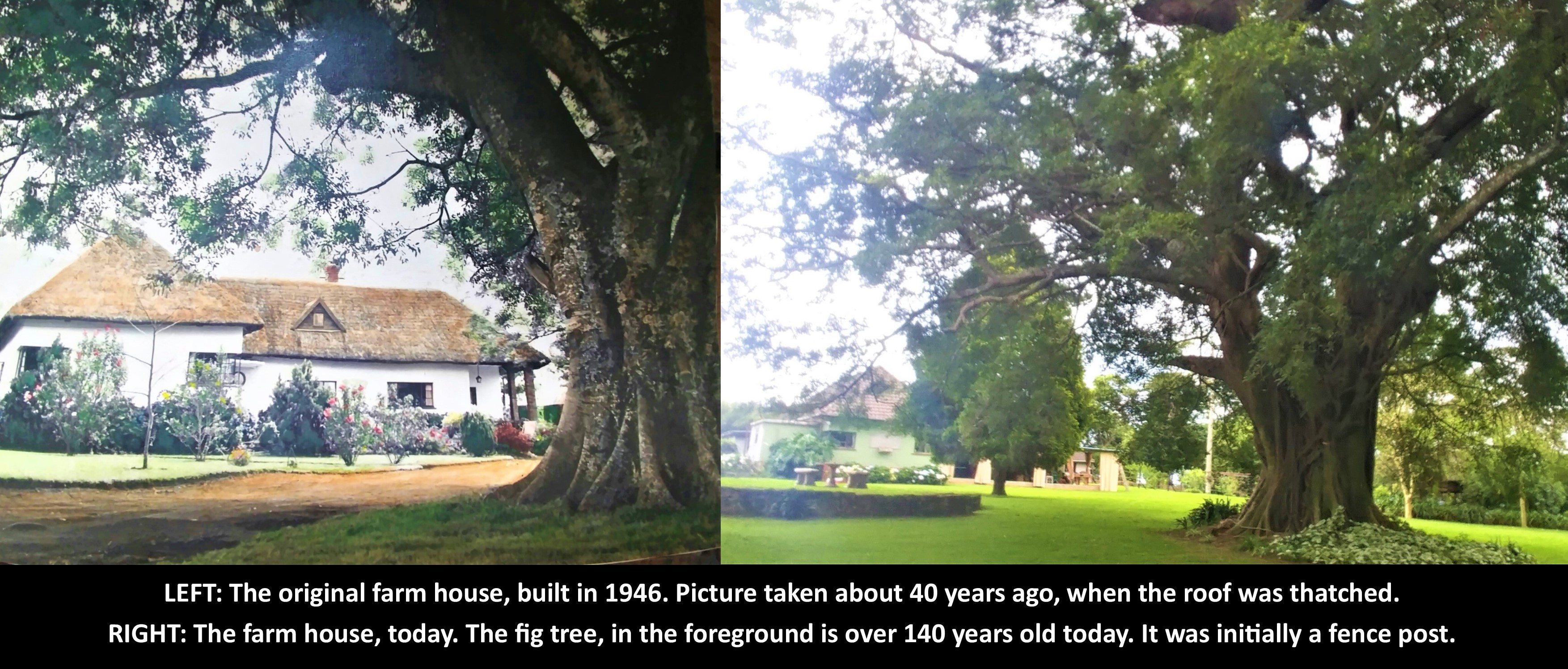

Mayfield Farm has a rich history; Piers being the third generation of his family to have the honour of farming here. It all began with his grandfather, who used to farm sugarcane in Cuba but during the turbulent Cuban revolutions and independence in the 1930’s, foreigners were chased out. Mr Garnett snr. went back to England but missed the sunshine and sweet grass too much. By randomly dropping his finger to a point on the world map, he chose South Africa as his new home and started working for Doringkop Sugar. In 1942, during his employment here, he bought Mayfield Farm, spending his evenings and weekends building it up and destumping (on horseback) large wattle plantations. There was a small cottage, which had served as the Thrings British Outpost in the 1880’s but a new farmhouse was built in 1946 and the family moved in. Piers’ Dad, Chris, was 8 years old then and attended Treverton School. After school, he travelled extensively, working on farms around the world. When he came home, his Dad divided the farm into two 80-hectare parts. Chris bought 80 hectares from his Dad and took over farming the full 160 hectares for them both.

Enter Piers, who had completed High School in Stanger, done his national service, spent time in England, dabbled in electronics and fitting and turning and completed a course at Agricultural College in Nelspruit. With all this experience and the farm recently having had a new section added to it, it was time for Chris to call Piers home.

By this stage, Piers had met the love of his life, Dominique, and they were ready for a new adventure together – the family farm was perfect for that. No handouts here though – just as Chris had bought the farm from his father, so Piers has had to buy it from Chris. Paying for something multiplies its value a hundred-fold. Piers is passionate about preserving this precious heritage.

FAMILY

Piers is one of four children. I am sure many of you know his brothers – Craig, who runs the business Chris established when he invented the Mayfield Applicator, and Miles, who is also a sugar cane farmer, managing several large estates. They also have a sister who lives in England.

Dominique and Piers have had three children – Gabriel-Reece who is 14 years old and 12-year-old twins, Sebastian-Jude and Noa-Grace. The family are kept busy with the children’s education and varied activities which include surfing, skating, trail running and motorbike riding, as well as learning many other skills like pruning Macadamia trees and land prep. Gabriel has planted his first crop of 3000 cabbages! And if the busy lives of the three tweens isn’t enough, Dom also runs her own Psychology practice in Ballito. I am sure, by the end of this article, you will agree that somehow, the Garnetts have secured an additional 10 hours in their 24-hour day. They do have the support of 4 grandparents though – both Piers’ parents and Dom’s mom and step-dad live on the farm with them.

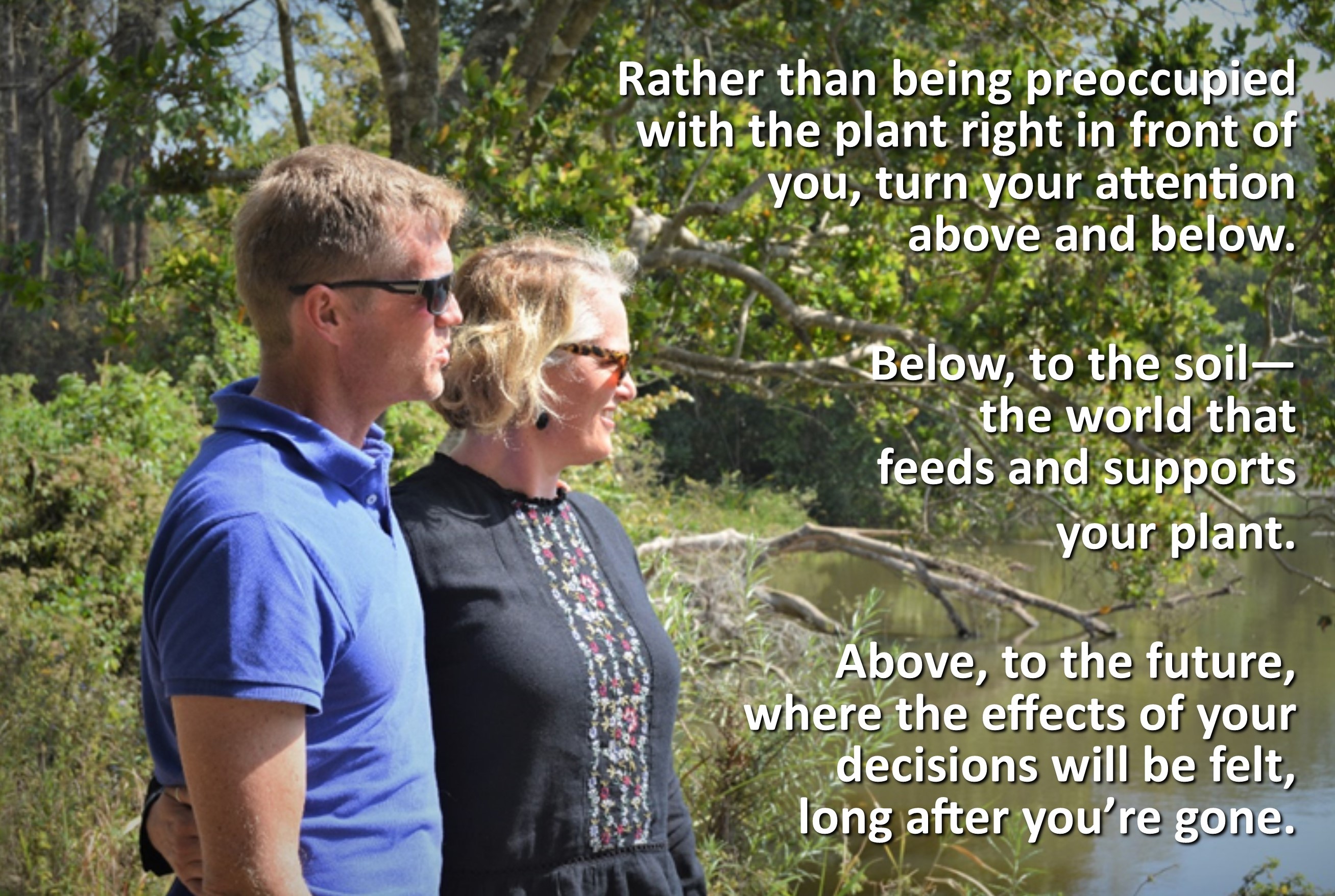

TRASH TALK

Now that you have the scene set, let’s get down to the details of Piers’ cane farming. Trashing has been practiced here for over 70 years. Every generation has been passionate about the contribution this practice makes to soil health and the results (both in environmental balance and financial return) support the motivation. But, it goes a step further than just trashing – Piers preserves the environment, both above and below the soil, as much as he possibly can. Monocropping is a sure way to unbalance things so, it takes a special commitment to the environment to try and mitigate the effects. He also believes in producing wholesome food. This way of farming is not the popular way, the cheap way or the easy way, but he convinced me that it is the right way.

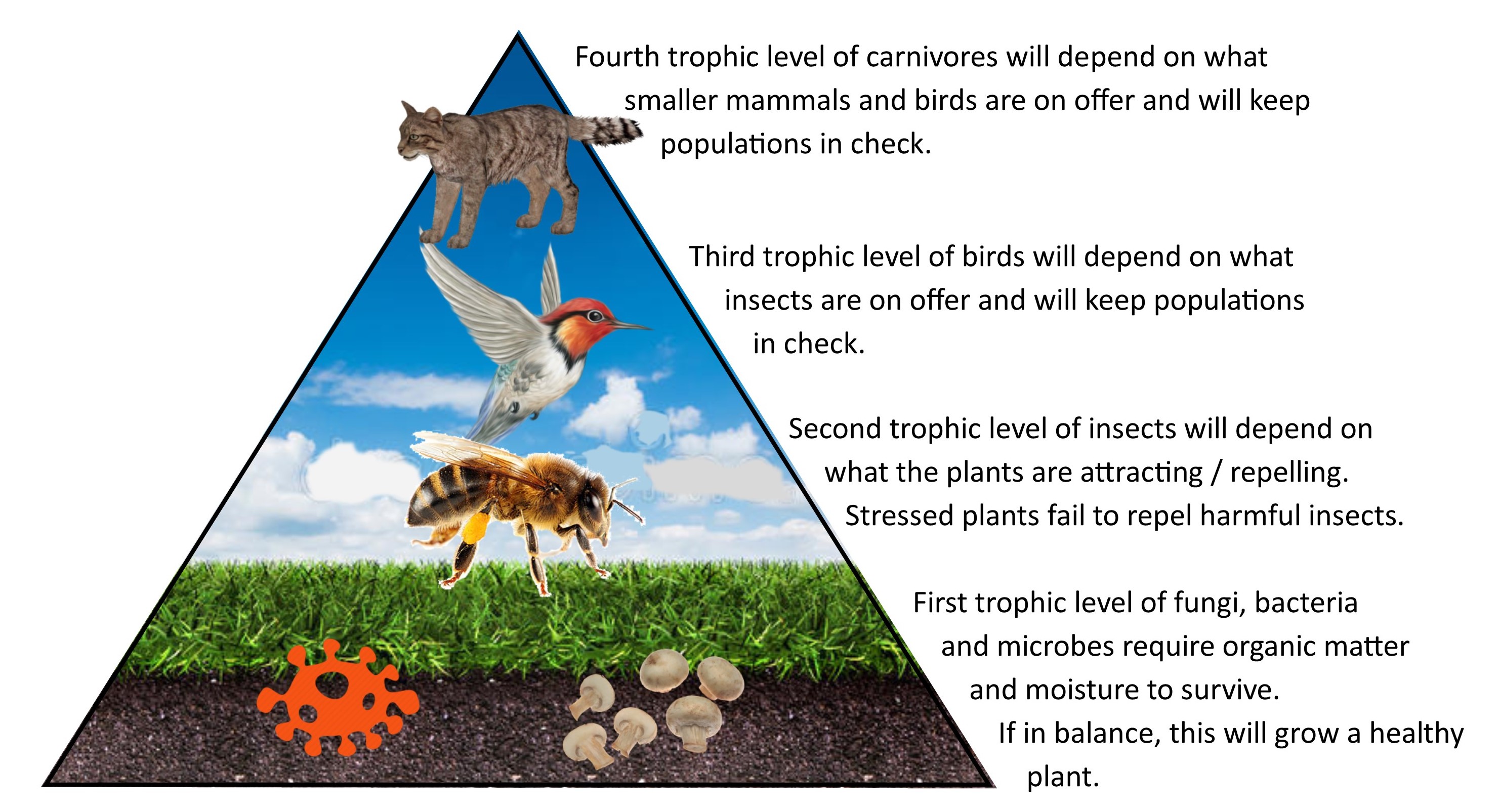

Farming is unique in that it relies on the wonderful magic of LIFE to turn small seeds into tonnes of food. When our ancestors left that magic wand in Mother Nature’s hand, she saw to it that there was balance, and all the organisms played their part. But when commerce and greed stepped in and wanted more food, faster, it grabbed the wand from her hand and used it to create man-made accelerators: sprays for insects, fertilisers for speed, more sprays for plants that got in the way. We also drained the soil – robbing it of all organic matter. All those chemicals and plunder have unbalanced the system. Crops got weaker, insects got aggressive, harvests were down, so, we used the stolen wand again and produced more synthetic potions. Now, farming has become a war zone – a constant battle against pests, diseases and drought.

All that the Garnetts have done, here on Mayfield, is hand the wand back to Mother Nature so she can weave her magic. Piers doesn’t pretend to understand the intricacies of all nature’s secrets but he has accepted that it’s a better way to farm. He starts at the bottom:

Soil: The whole motivation behind trashing is that, instead of burning off the leaves the mill doesn’t want, they are left in the field. This is the simplest, cheapest organic matter available to the cane farmer. The leaves decompose creating a life-sustaining environment (full of moisture and microbes) that will feed your crop. Simple, but it’s only the first step. Once this life-filled substrate is working efficiently, you need to protect it. The harsh chemicals applied to kill weeds above the ground don’t find their way back into the hazmat container they came from once the job is done. They seep into the soil where they sterilise life there. So, now you have dry cane leaves, and nothing to turn them into natural fertilisers. Pointless. To illustrate this point, Piers told me about a farm he visited once; while digging in a field that had been planted 13 years prior, he discovered a fully preserved stick of cane – it even had juice! The soil was so completely void of life that the cane had not even decomposed. Needless to say, the farmer had been struggling to farm in this sterile sand that retained absolutely no water.

Farming the way Piers does takes a revolution. “But it doesn’t have to be aggressive or instant,” Piers laughs, “Take it slowly. Convert 10% of your farm each year, starting with the most marginal fields. Allow the time this process needs to happen. It’ll take 3, or even 4, years to see the benefits.” And therein lies the challenge. No one has 3 to 4 years! We are all wired on instant gratification. Like impatient children, we want it to happen NOW! Therefore, although this is the most logical and practical method to follow, it’s not the most popular. Piers is thrilled that 70% of the Doringkop group of farmers are now trashing, and reaping the benefits of lower input costs, higher pest resistance, much higher drought resistance and a healthier, heavier crop.

So, how does a trashing farmer deal with some of the challenges burning farmers perceive in the practice?

- Lower sucrose. Burning may raise sucrose levels slightly but it’s marginal. What’s far more beneficial is the much higher volume (mass) that trashed cane attains. You won’t be any worse off on pay day, when it comes to sucrose gained through fire vs a better volume.

- The cutters won’t cut unburnt cane. Piers’ cutters now whine when they have to harvest a burnt field. They love trashing where they don’t have to breathe, chew and look through curtains of soot. Yes, some varieties have annoying hairs but you simply avoid planting those. Incentives are always an excellent motivational tool and Piers suggests they be implemented to get through the first few weeks of harvesting trash fields. Thereafter, they’ll chose trash over burn. Piers’ always manages to keep cutters because every year they know they’ll have a farm that is producing good cane. The drought highlighted this on Mayfield and this year Piers has cutters from far afield because the cane is so poor elsewhere. He pays R40 per tonne, trashed and stacked.

- Mill resistance. Yes, mills do not like trashed cane because it slows down the process of milling. The sugar industry, although unified, has two very separate parts. One is agricultural and the other is industrial. It is strongly arguable that the agricultural and environmental benefits of trashing far outweigh the industrial challenges of milling trashed cane.

- New ratoons can’t break through the trash blanket. Although Piers hasn’t had to part the trash in the last 5 years, he did do this to combat the issue previously. It’s a simple job and the trash benefit to the soil is far greater than the hand units it costs to part the trash.

- Trash gets blown away. Just like you have to watch the wind before you burn, so too with trashing. Piers also tries to make sure there’s a little bit of moisture on the ground when he trashes as this helps it ‘stick’. “But, every year, there’ll be 5 to 6 hectares that blows away. It’ll collect on the nearest fence or trees. I just wait until the wind dies down and there’s a spot of rain, then I go and fetch it and put it back where it came from. The labour units it takes is paid back ten-fold by what it adds to the soil. It’s only a couple of weeks before the ratoons come through and the trash is held in place by the cane.”

If there are any other areas that any farmer would like discussion on, I would be happy to get Piers’ perspective.

The recent drought reminded Piers of how much value there is in trashing. Having experienced no yield decline the first year, he cautiously reduced estimates in year 2 thinking that there had to be some casualty in the extremely dry conditions. He was blown away when all his estimates were exceeded handsomely. “It never would have happened if the soil wasn’t holding on to so much moisture, thereby sustaining the health of the plants.” When he had to witness his compatriots in Darnall and on the coast lose so much, it fuelled the fire to keep trying to convince them that trashing would benefit them even more than it does him. “They have the heat units that I don’t get, being 35kms inland. These heat units help the young ratoon cane break through the trash blanket quickly.”

WEEDS

Piers loves weeds. They are an important part of his farming operation. (Even I was looking at him strangely after this declaration) But once again, it makes perfect sense:

- Weeds are sacrificial plants. As part of maintaining a healthy, balanced ecosystem, there has to be something for the next tier of the food pyramid to eat. If you don’t want it to be your crop, best you provide something else.

- Weeds are indicators. By studying the plants (both present and absent) in a field, you can tell what it has enough of and what it is lacking. Piers also farms organic macs (more on that later) but when the organic certifiers came to inspect, they paid very little attention to the macs, preferring instead to examine what else was growing in and around the orchards. They explained that the other plants (we generalise and call them weeds) tell them all about what’s been going on. Obviously, they were looking for evidence of chemicals but we can learn to speak this “plant language” and use it to understand how to supplement the soil and produce a better crop. Kind of like reading a soil analysis report that covers every square metre of your field, for free!

- Weeds work. I know kweek (cynodon) is a swear word but nature uses this plant and its rhysomes to break up compacted soil. Piers is not suggesting that you sell the ripper and plant cynodon but rather that you read the sign – that area requires aeration. This makes perfect sense when you think about the fact that cynodon is most commonly found on the edges of the fields and in high traffic areas.

Having said all this, Piers does have to draw the line somewhere. His perfect scenario would be to hoe every weed back into the soil but cane does not make enough money to warrant that volume of labour. Instead, he compromises by applying only one spray with a soft herbicide that he has researched thoroughly. The rest is hand weeding or spot spraying. The thorough research Piers recommends is to assess the residue side effects of the herbicide. As already mentioned, chemicals do not go back into the drum they came from after killing the weeds, they stay on your field and seep into the soil, causing devastation and death. Mitigate that risk by establishing what the residual risks are. It’s usually measured on a scale of 1 to 5 but it’s not easy information to find. Remember that anything that kills fungi is dangerous to your soil health.

A clear illustration of how poisons don’t vaporise, and have to go somewhere, was experienced here recently: Glyphosate was found in bonemeal that Piers almost bought to use in the mac orchards. The only explanation for its presence is that RoundUp ready grass had glyphosate residue on it when the cattle grazed.

For trashing to be truly effective, it needs to work with the softest available herbicides. Soil sterilised by chemicals will not benefit your crop, regardless of the organic content, as we learnt from the 13-year-old mummified cane stick.

As we know, ripeners are herbicides and Piers avoids them because of their effect on the environment. His RV’s run at slightly below mill average, but, his tonnages are way above, compensating for the lower RV, keeping his operation financially and environmentally healthy.

FERTILISERS

Piers uses SASRI for soil and leaf sampling and applies fertilisers. Again, this is an area to which he applies restraint and careful thought. Soil sampling results will tell you what’s in that clod of soil, but it’ll not be accurate for a clod 20m away, neither will be it be a completely accurate comparison to the sample you took last harvest, which might have been 15m east of the spot you stand now. It’ll also only tell you what is in the soil, and that might be different to what is available to the plant. For this reason, Piers also has leaves sampled, thereby gaining understanding into what soil nutrients the plant has been able to use. Cation exchange tests are also useful in this regard as they show what is present and what is accessible.

The Mayfield applicator is obviously the tool of choice, not only because he gets a good family discount but also because he allows no vehicles in his fields unless it’s to collect the harvest. Granular application works well on trashed lands as the grains bounce off the trash and prevent banding so commonly experienced on burnt land. In an effort to minimise the effects of volatilisation, Piers did use liquid fertilisers during the drought. Although he has turned to LAN based products recently he still prefers to fertilise in the rain. Sunny days are saved for herbicides.

Lime and gypsum is recommended by Piers – it can’t hurt anything and assists in remedying the effects of monocropping.

What about break crops? Piers uses madumbies or sweet potatoes because they provide a little cash flow and they do a great job of loosening the soil structure, providing subsoil organic content and nitrification. After a year of this he’ll often leave the field to a six to eight-month ‘bastard fallow’ where all weeds are welcome. Either that or a winter oats or a summer crop. 18 – 20 months seems like an excessively long break to give a field but when you consider that some of Piers’ fields are in the 36th year, it’s nothing. Yes, I did verify my hearing – 36 years and still going strong. Every harvest, he thinks will be the last and then the field exceeds estimates and gets to stay another year. Another cost-saving point to trashing!

A field that recently had its bastard fallow worked in.

While on the point of cost saving, Piers says that there have been years when he hasn’t fertilised some young ratoons at all, and some where he has only done one half of a split application. The rich soil will allow you this grace but Piers says that you can’t neglect the fertilising task completely, over a period of more than a couple years. Monocropping drains the soil of certain elements that have to be replaced periodically.

MECHANISATION & HARVESTING

Piers harvests only 63 – 65% of the farm each year resulting in lots of carry over. The average growing cycle is 16 to 17 months.

He is fanatic about protecting the subsoil environment and no one even walks in the fields unnecessarily, let alone drives a vehicle through them. Because of the years of trashing, the soil is soft and spongey permitting more damage to the plants therein than what hard, dry, sterile soil would when tractor tread rolls through it. When the tractors are allowed in to collect the cane stacks after harvest they always turn down the field, never up, and leave efficiently. Lip channels are used to stack the cane onto. These prevent the need to dig furrows for the cables that load the stacks. Piers’ farmer group established that this practice can save 10% of the crop which would otherwise be lost when the ratoons are damaged and soil erosion sets into the furrows.

We discussed earlier, the long life of Piers’ ratoons but he is forced to remove a certain percentage of the farm every year to accommodate the stock supplying his busy seedcane business. This seedcane operation not only provides a neat income, it also keeps his labour employed for part of the off-season. Piers has a Heat Treatment Plant where he cooks the seed in February. That leaves March for maintenance before the season starts again in April.

How does he decide what to plough out? A formula of tonnes per hectare per month gives him a guideline. If the result is over 5 or 6, the field stays but anything below that usually goes. So, a 17-month-old crop, producing less than 90 tonnes per hectare is borderline. (90/17 = 5.3) He knows that some consider his criteria a little high, preferring to only plough out when they get a 4 or less but Piers expects (and is used to getting) more.

Trashing cane means that you have to watch the base cut during harvest because the leaves that have been slashed off the cane will be lying on the floor, obscuring the base. He trains cutters to cut into the soil, thereby ensuring a nice low cut. It does mean that knives need extra sharpening but remember that the soil is softer so it’s not too much of a problem. The cane is then stacked onto the rails with the tops facing outwards. No one gets a ticket for their stack until inspection has cleared them of ineffective topping. As much of the trash as possible needs to stay in the field.

A side loading trailer then collects the stacks. They go for weighing and release on the loading zone where a Bell loader fills the trucks.

ALTERNATE INCOME STREAMS

Piers is building a ‘three crop farm’ that works together, creating a balanced whole.

Sugar cane is the cash crop and will always be the largest sector. Macadamias are a long-term investment that requires a specialised labour force. It works well to fill some of the sugar off-crop season. Filling more of the sugar off-season is a shorter-term investment – Essential oil farming and distilling.

Macadamias

Piers started macs 24 years ago. Not because he was a visionary, but rather because he came across the tree whilst at Agricultural College in the Lowveld and he “liked the look of it”. So, every holiday, he’d load up to 40 saplings into his Toyota Corolla and head home. There are now 10 hectares of macs on Mayfield, all organically certified. No sprays or chemical fertilisers whatsoever. He does use organic feed such as bone- and bloodmeal but that too, has to be certified free of any chemical contaminates.

Essential Oil

At the moment Piers has 8 hectares and is planting another 4 in 2018. He plans to extend this to 25 hectares as capital becomes available. He says it’s a great crop to plant on his arson fronts because it burns reluctantly. Cattle don’t like it either.

PESTICIDES AND BALANCE

Piers has made the decision that no pesticides will be used on Mayfield. There really isn’t a need. The Eldana issues are limited to the marginal fields that are regularly subjected to arson, reinforcing the fact that burnt fields are more stressed and therefore more susceptible to infestation. Healthy plants emit a hormone that repels unwanted pests. Stressed plants are not strong enough to emit this hormone and fall victim.

No burning also means that natural predators thrive in the fields and keep all insect numbers in check.

Piers’ farm is not immune to pests and he does have occasional damage because of them. But he tolerates that loss and leaves the insects to move along naturally, which they always do. “You will suffer losses when you farm like this,” Piers explains, “but I’d rather endure the odd loss from short term, natural phenomena than devastating unnatural sterilisation that causes incalculable long-term losses.”

ADMIN

Pier is a visual person, preferring to see his whole farm laid out on a large pinboard across the whole wall of his office. On this, he keeps careful records about each activity, harvest and other historical detail pertaining to each field on the farm.

Reluctantly, he spends rainy days or evenings in the office but during the day he can normally be found walking, cycling or (on a lazy day) motorbiking around the farm. He has only one Induna so most of the hands-on management is done by Piers. He does all the basic paperwork, handing over to local accountants for book keeping and Durban-based auditors for wrapping up.

When it comes to managing people, Piers cannot over-emphasise the value of listening. Africa appreciates the investment of time. Just like all of nature, we are meant to have more patience. Although it seems suffocating, you need to take a deep breath, a seat, and listen. He insists that, in the long run, it’s worth the sacrifice.

Piers also does all he can to keep people employed throughout the year. He has third generations of family living here and they value the effort he puts into creating regular incomes for them all. That input on Piers’ part is rewarded in loyalty and commitment.

GIVING BACK

Because of Piers’ success as a farmer, he has many people visiting the farm to learn from his practices. He wishes more people would implement what they learn, and continues to trust they will. That’s why he entertained this SugarBytes interview. We hope that many farmers consider a more environmentally-friendly and long-term view of their farming operations after reading this.

Some people are skeptics and Piers entertains them too. One such farmers came from Eshowe a few years back. Piers met him out in one of the fields when he arrived but the visitor got out of his bakkie with a sharp metal object in his hand, walked straight past Piers and launched the javelin-like tool into the air. They both watched it descend and peg into the soil firmly. At this point, the farmer turned around, smiled and introduced himself saying he was glad he’d found the right farm. He wasn’t about to take advice from a farmer whose soil bounced the javelin.

Piers also hosts university students who need to complete their 6-month pracs on a farm. Although the government is supposed to pay them, it usually falls to Piers to compensate and provide housing for them while they learn about being responsible custodians of the soil under his expert guidance. It’s his investment in our future.

WRAPPING UP

Piers’ parting pearls:

- When faced with a challenge, investigate and deal with the cause behind the symptom instead of treating the symptom alone. You’ll probably find a longer term, more cost-effective solution that way, and one that minimises harmful side-effects.

- Look after the little things – the microbes living under the soil, and the big things – your plants, will take care of themselves.

- Successful farming is based on good water and soil management. If you provide a safe environment, where these elements are protected, you will be rewarded with a healthy crop.

- To see one’s self as a Custodian of the land – having an ethical responsibility to farm in a way that is as kind to the earth as possible and to be respectful of one’s position and ethical standpoint towards the land and people who work it.

I loved spending time at Mayfield. I found Piers’ way of farming to be wholesome and balanced, devoid of greed and stress. He and Dominique are grateful and content with the “enough” that they enjoy and protect for future generations.