Almost all the farmers I visit are diversifying – anything from live chickens to a B&B on the property. Second, third and sometimes even fourth income streams are becoming the norm. But, when we talk about norms, nothing is more normal than finding a sugar farmer who also has a finger in the “mac-pie”, or plans to get there soon. Macadamias and sugar cane share the same climatic preferences and therefore live happily together, they also integrate nicely in terms of off-seasons so that staff can easily be cross-skilled to participate in the care of both crops.

Almost all the farmers I visit are diversifying – anything from live chickens to a B&B on the property. Second, third and sometimes even fourth income streams are becoming the norm. But, when we talk about norms, nothing is more normal than finding a sugar farmer who also has a finger in the “mac-pie”, or plans to get there soon. Macadamias and sugar cane share the same climatic preferences and therefore live happily together, they also integrate nicely in terms of off-seasons so that staff can easily be cross-skilled to participate in the care of both crops.

So, what am I on about macs for? Isn’t this SUGARBytes! Well yes, but I have had more than one call to delve into this nutty world so, just like we went down the road named INNOVATION in the last story, this time we are going to amble down DIVERSIFICATION Drive. It’s all still very relevant to supporting successful sugar cane farming, especially with the current sugar price … so, here’s what I’ve found out about farming macadamias:

HISTORY AND BACKGROUND

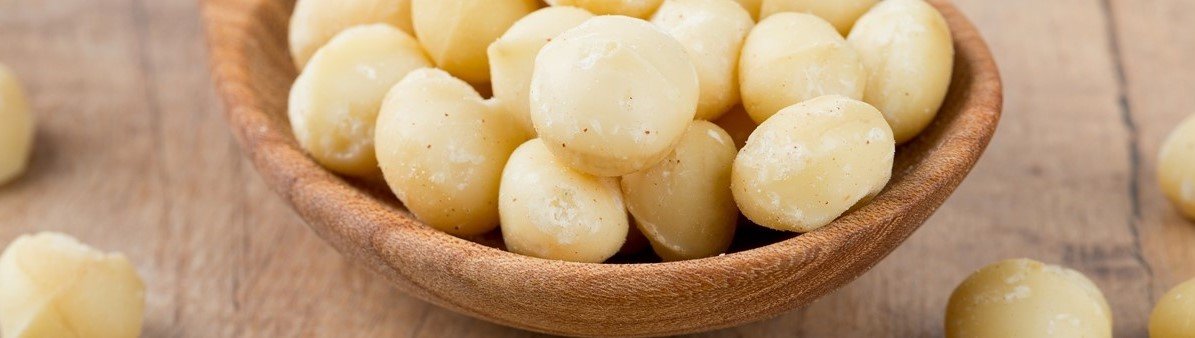

Macadamias originated in subtropical eastern Australia, Indonesia and New Caledonia. They were first introduced in SA in the 1960’s. It’s a very versatile nut used in making snacks, ice cream and confectionery. Its oil’s rich, cushiony skin feel and high oxidative stability make it especially suitable for heavy creams and sun care formulations as well.

South Africa competes with Australia as the largest producer of macadamia nuts. The 2018 World Nut and Dried Fruit Conference estimated a yield of 53 500 tonnes, with a sales value of R3,2 billion for the South African industry in 2018 – that’s about R60 000 per tonne. As with everything, the price is driven by the demand which is currently high, mostly due to China’s growing consumption. 30 to 40% of SA’s macs end up in China at the moment. In 2017, China produced 10 000 tonnes of their own macs and that will obviously increase year on year, reducing demand and therefore price but, at R60 000/tonne, there’s a way to go before growing the crop loses its appeal. All that’s happening now is that it’s becoming a buyer’s market, and by that, I mean that buyers can now get a little fussy on size and quality of the nuts they purchase. As with most things, South Africans do it well and our nuts generally meet the picky quality standards so the demand has not slipped yet. Besides China, Europe, the US and Canada are also large customers. Driving the demand for nuts is the fact that more people are eating less carbohydrates in favour of plant-based proteins and oils.

When we talk about possible market saturation, I was interested to learn that macadamias form less than 1% of the global tree nuts consumed; looks like there’s room for growth there too.

Currently the SA mac industry is employing 12 500 people including seasonal harvesters and processors.

INDUSTRY STRUCTURE

As with sugar, there is a support structure for the industry; SAMAC (Southern African Macadamia Growers Association) represents growers, processors and marketers. They collect levies which are used to, amongst other activities, provide training, conduct research, run workshops, improve quality and competitiveness as well as access to global markets. They also disseminate information to the industry. Pretty much like our SASA does …

As far as marketing your produce, it seems that there are a few companies that will sell on your behalf: I found Green Farms Nut Company, Valley Macadamias as well as Mayo Macadamias and Ivory Nuts.

BASIC FACTS

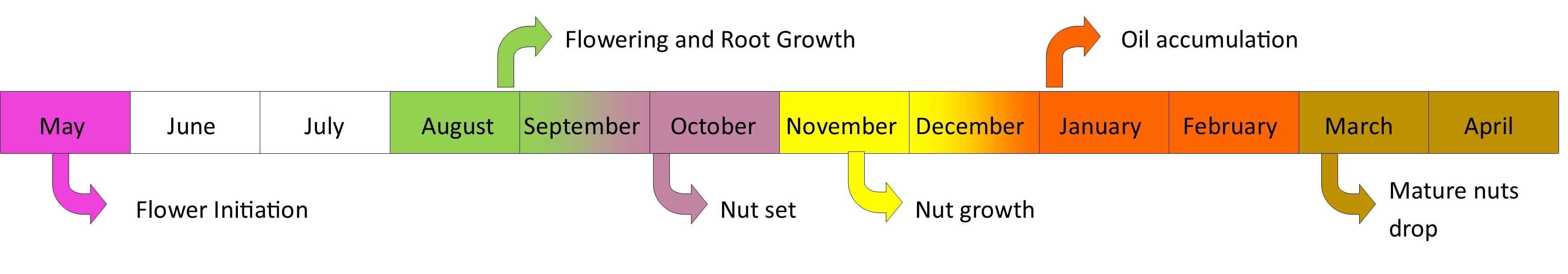

- Those of us who are used to planting sugar cane and watching it grow tall enough to cut, with one exciting stage being when it canopies, can be a little overwhelmed by the phenology of the mac tree. Just the word made my eyes blink uncontrollably. But, that’s what this article is here to do – introduce you gently to the nut-world … Phenology is, quite simply, the study of a plant’s growth processes throughout a one-year cycle. And this is what the mac’s phenology looks like:

I’ll explain more on each stage throughout the article. NB: Behaviour differs slightly between the various cultivars (varieties) .

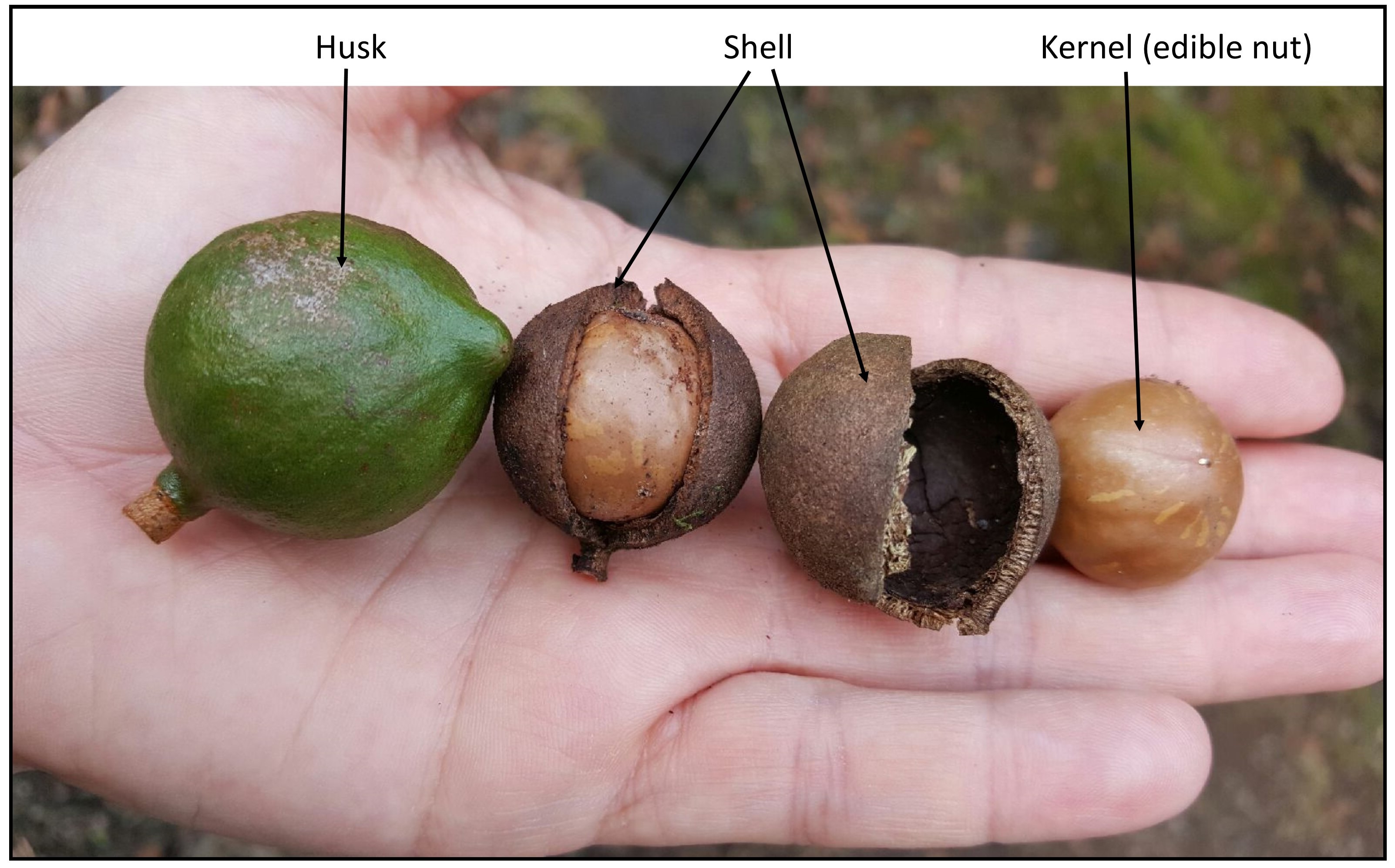

- The ‘fruit’ is sold either as NIS (nut in shell) – Asia usually takes it this way, or as kernels (deshelled nuts) – which is how the US & Europe prefer to buy it.

- ‘Crack out’ is the measure of quality. It is the kernel (edible nut) as a percentage of the whole dry-nut-in-shell weight. High crack out (and therefore less shell) is the target. It seems that a fairly good crack out figure is 35-40%, which just goes to show how incredibly large, dense and heavy those shells are!

- High nut quality and production is best achieved at lower altitudes. That’s not to say that macadamias cannot be grown at higher altitudes, as we see in Mpumalanga (which is currently SA’s largest mac producing area, followed by KZN and then Limpopo), but if they are, then microclimates need to be managed ie: select slopes with a suitable aspect and consider micro-spraying irrigation to increase humidity.

- Humidity has a positive effect on the growth and crack out of the macadamia. Tropical or sub-tropical climates (16 to 25’C) are therefore most suitable. Frost will damage the flowers which lowers the fruit set. Too cold and the shells thicken (lowering your crack out %), too hot and photosynthesis slows down. So, if you’re growing avocados, papayas, mangoes or bananas successfully, the chances are that macs will thrive on your farm. Interestingly enough, I am currently visiting farmers in the Komati and Malelane areas and have discovered that trials here (where it gets up to 50’C in summer) are doing brilliantly ie: don’t count yourself out if you live in a hot area, but do focus on your micro-climate control if you’re considering getting involved.

- It seems that if you produce anywhere from 3,5 to 4 tonnes per hectare from your mature mac trees, you’re doing well.

CULTIVARS AND OPTIONS

In sugar, we call them varieties, mac-people call them cultivars. As this industry is not as old as sugar is in SA, knowing exactly which cultivars are best in which areas is not yet completely clear. The popular options seem to be Beaumont and A4 followed by Hybrid, Integrifolia, 849, A16, 816, 814 and Nelmak 2.

As with sugar cane, it is advisable to plant 2 or 3 different cultivars. A consideration when selecting which cultivars to plant is how you want to harvest; herbicides can be used on some cultivars to reduce the labour component of harvesting. In these cases, mechanisation can play a greater role. Unlike sugar cane, pollination is an essential part of producing a crop. Macadamias require bees (or other small insects) to handle their pollination (and the subsequent production of fruit) so this brings in a whole spectrum of new considerations for farmers; like pesticides and the general wellbeing of a new workforce (the small pollinaters).

As cross-pollination between cultivars will occur, and is actually beneficial to the orchard’s production, it must be considered when selecting cultivars ie: synchronized flowering. Beaumont and A4, two of the most popular cultivars, do coincide nicely.

ORCHARD PREPARATION AND ESTABLISHMENT

Get your cheque book out, no need to sharpen any pencils – this is not going to be cheap! Excluding implements, it is estimated that it’ll cost R100 000/hectare to establish an orchard. And then, annual running costs (weeding, fertilising and irrigation) will average at R 25 000 per hectare per year.

There are many nurseries that have sprung up since macs became popular but it is possible to propagate your own trees. The trouble is that if you do, and it goes wrong, there’s a lot of investment at risk.

Most soil types are suitable for the production of macadamias, provided they are well drained and have no restrictive layers in the top 1m of the soil. Poorly-drained clay soils are not suitable.

It is not advisable to fertilise recently planted trees. They must first become well established and grow vigorously. The advice is to wait up to a year before applying fertiliser.

A successful tropical fruit and sugar farmer in Mpumalanga found this out the hard way. When preparing his first mac orchard, he placed 25kgs of kraal manure in each hole, as is standard practice with all the fruit trees he plants. A week later, the leaves were curling and it was clear that something was going horribly wrong. They quickly pulled all the trees out and replanted, without fertiliser. Below is a pic of this orchard, that is now recovering well from its rocky start. SugarBytes is all about learning from successes and failures and we are grateful to Grant Taylor, for sharing this experience, and showing the results so that similar disasters can be averted for others. More on this amazing Komati farmer in a few editions time …

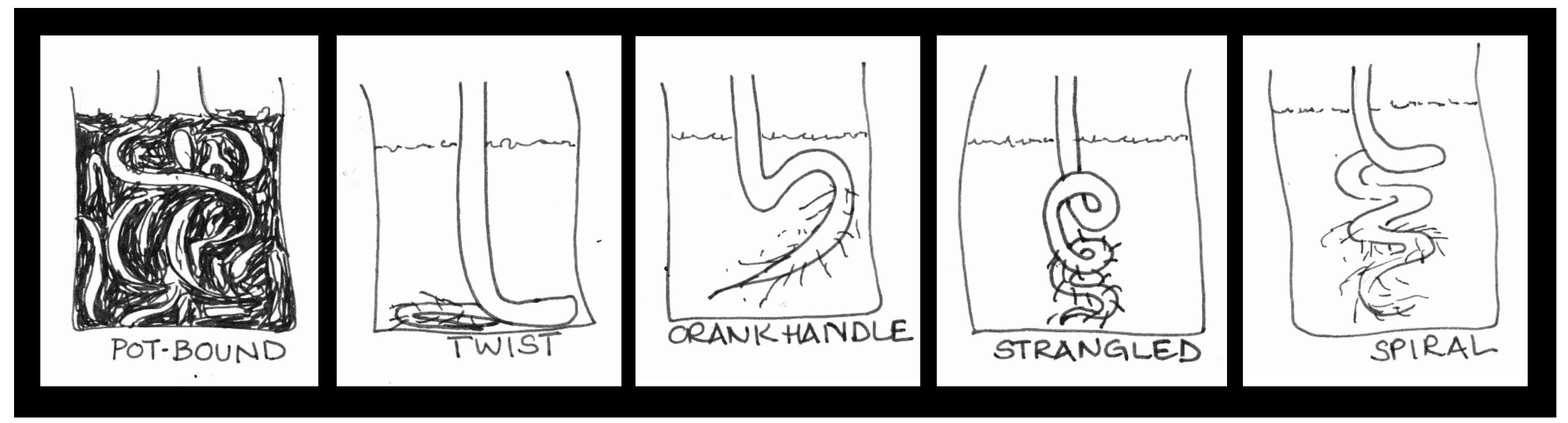

When visiting a nursery, select high-quality trees by inspecting the plant container and roots. The size of the container is very important. If the container is too small, the tree becomes pot-bound and the taproot might be distorted. The tree may appear healthy in the nursery, but has little chance of reaching its full potential in the orchard. The weakened root system cannot provide the growing tree with sufficient water and nutrients. A well-developed root system will look something like this:

Whereas poorly developed root systems take on many forms, some of which even have names:

Other factors that you should check out are: the soil mixture, leaves, internodes, the graft union and the shape of the tree. This last characteristic influences how closely together you plant your trees; some trees grow tall and narrow whilst others tend to be shorter and wider (vertical vs lateral growth). Regardless of this factor, pruning is important. And whilst on the topic of pruning, it is another chore you need to carefully consider when assessing this venture – how much do you want to be maintaining and trimming your orchard to ensure optimal sunlight infiltration while minimising labour costs. And even more importantly, but inextricably linked, is your anticipated per hectare yield. It’s becoming clear that planting is even more of a ‘gedoente’ in macs than it is in sugarcane, but, as the average productive lifespan of a mac tree is 40 years, it’s worth doing well, so let’s go over a few of the details more carefully:

- Different cultivars have different growth patterns. Some grow in an umbrella shape ie: more lateral, whilst other will tend to be taller and narrower.

- The size of each cultivar’s drip area (surface area below leaf canopy) depends on the altitude, soil type, rootstock, rainfall, temperature and relative humidity. The planting distance for each cultivar will therefore differ from place to place.

- As soon as the competition for light becomes too great, production will decrease.

- To allow for tractors to move between the trees, the hedgerow planting system is used. With this system, upright growers are planted 3,5 m apart within the row with 7 m between rows. Spreading cultivars are planted 6 m apart within the row with 10 m between the rows.

- Something else I learnt in Komati (thanks Chris Gemmell) is that, as a part of managing micro-climates in a hot area, you can plant rows east-west as opposed to the normal north-south which allows maximum sunlight penetration. By reducing sunlight penetration, you lower heat and cool the orchard. Micro-climate managed!

NURTURING YOUNG TREES

Intercropping, where other crops are sometimes cultivated between young macadamia trees, is common practice but these factors should be carefully considered beforehand:

- Intercropping with a quick turn-around crop means you make a bit of money from the land while the macs are growing to bearing age. But, once they’re bearing, the macadamia trees should receive the attention and treatment necessary to ensure maximum growth and production.

- Intercropping creates a wind break for the fragile young trees.

- Cultivation of the intercrop could damage or adversely affect the growth of the tree or injure roots and should be avoided.

- Tall-growing plants could crowd out or overshadow the young macadamia trees and should not be planted.

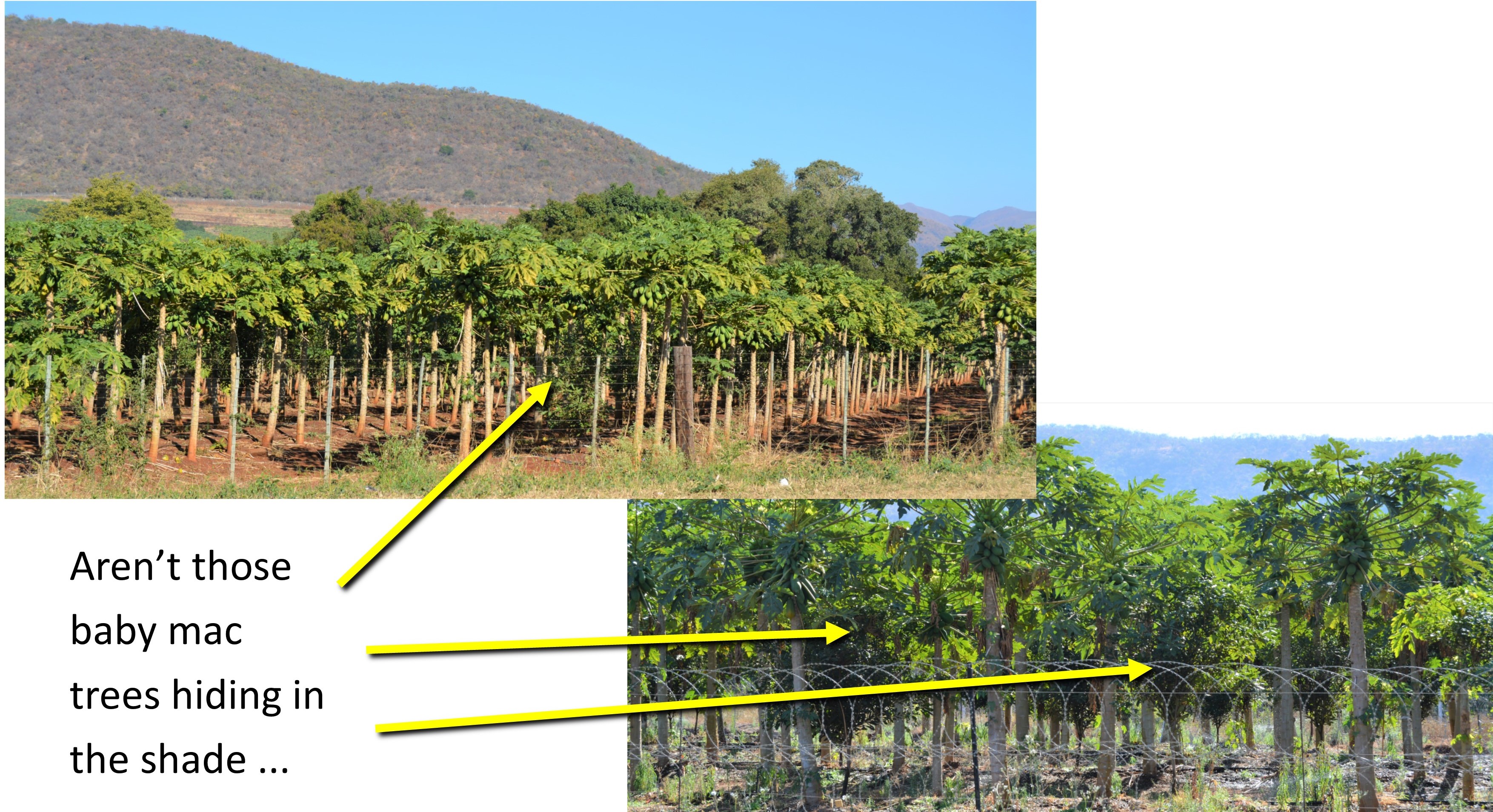

Bruce Zunckel has been successfully intercropping with what he knows best – sugarcane. (Pics above and below) He trashes this cane and uses the trash to mulch the trees. It’s been a win-win all round and, he says, almost covered the costs of establishing the mac orchards whilst also providing effective wind-breaks when the trees were small.

Ant Goble chose to use a fodder instead (pic below), the advantage being that it is far more fire-retardant. The disadvantage being the lack of income.

Somewhat contradictory to the advice to not plant in the shade of a taller crop, I came across this orchard whilst driving along the N4 in Mpumalanga – looks like pawpaws (yes, I am sure there is a much more scientific name) and baby macs in the shade. But maybe it is part of a strategy to manage the micro-climate and protect the young trees while they establish themselves in this very hot area …

EQUIPMENT

In order to preserve the produce and conserve the quality, Macadamia farmers need to dehusk and dry their nuts as soon after harvesting as possible. These two pieces of equipment seem to come in many shapes and sizes, with many being home-made in true ‘boer-maak-‘n-plan’ fashion, but here are the main requirements:

- Dehusker: Dehusking should happen within 24 hours of harvesting to ensure you get the most from your nuts. The husk is high in sugars, and moulds soon develop if you get it wrong. This process simply involves removing the green husk from the shell. If it is ripe, then this happens fairly easily; the most rudimentary method being to place the harvested nuts in a bag and beat them. Obviously, machines have been built that make this process easier.

- Drying bin: Managing the drying process is essential to obtain tasty crunchy kernels (nuts). When the macadamia nut is first harvested, moisture content is around 27%. This has to be lowered to around 4% to crack effectively. Stage 1 drying is dropping the moisture content to around 14%. At this level those moulds causing kernel discoloration cannot survive. Forcing cool dry air through the macadamia nuts is ideal. In practice this usually means blowing ambient air through the macadamia nuts in a purpose-built drier, or leaving nuts in a breezy spot in onion bags. Macadamia nuts could also be laid out in shallow layers if the volumes are small, eg. on an old wire-wove bed. Indoors in a controlled environment is better, and avoid getting direct sunlight on the nuts. Rake over nuts regularly to ensure even drying. Stage 2 drying (or ‘curing’) is forcing warm dry air through the macadamia nuts. When relative humidity gets down to around 30% then some nuts should begin rattling in their shells. If heating to about 30 degrees can be added, drying is accelerated.

Besides the usual farming equipment of tractors, trailers, sprayers etc, these are the two pieces of specialised equipment required.

FEEDING & WATERING

The aim of any fertilisation programme should be to keep the plant and its root system healthy, and to replace, at least, the amount of nutrients removed each year by the crop.

According to Dr Gerhard Nortje, a fertiliser consultant and senior lecturer at the University of South Africa, a yield of 3,5t of nut-in-shell / hectare would absorb about 63kg of nitrogen, 3,5kg of phosphorus, 70kg of potassium, 17,5kg of sulphur, 35kg of calcium and 5,25kg of magnesium, per hectare per annum. Regular soil and leaf sampling will help to check whether the suitably high iron levels required by a healthy macadamia tree are present.

Split, well-timed, regular fertilisation gives the best results and it seems like the team at ND Goble Estates is turning this into an art form by drip irrigating the required nutrients to the trees; small quantities regularly.

It is also advisable to not apply any fertiliser to the newly planted trees until they have recovered from the planting process and the roots have grown beyond the planting medium, some sources say 8 weeks is sufficient whilst others recommended up to a year.

It seems that soil acidity, phosphorous and iron content are foundational to establishing a healthy mac orchard: the effect of high pH and high phosphorous levels on iron levels is disastrous for macadamia trees. Therefore, these need to be analysed and corrected during land preparation, before planting.

As cane farmers, we’re no strangers to lime and gypsum, which is also required by the mac tree. Optimal root development will also be facilitated by deep ripping.

Macadamias need lots of organic matter, so the incorporation of as much plant-matter-based compost as possible, up to 10t/ha prior to planting, is an added benefit, especially on sandy soils.

As we know, anything organic is more sustainable and Madumbi Sustainable Agriculture has provided supplementary information on this, specifically for macadamias. Use this link or go via their advert above to access it. You’ll remember the value that one of our very best sustainable farmers, Richard Cole, found in their products for his cane.

Never apply fertilisers against the stem of young trees, fertiliser should rather be broadcast evenly from about 0,2 m from the stem to about 0,5 m outside the drip area of the tree. As the trees are very sensitive to root damage, it is best to apply some light, controlled irrigation after fertilising, ie: fertilisers must not be worked into the soil.

Water stress often limits tree growth, as well as the set, growth and quality of macadamia nuts. It is important to know how much water to apply and when to apply it if it does not rain. On average, a tree will need between 40 and 120 litres per day depending on the age, cultivar and time of the year.

PESTS AND DISEASES

It seems that macs have their own ‘eldana’ but instead of a worm, it’s a Stinkbug! Stinkbugs are the most devastating pest for macadamias in South Africa. Stinkbugs can cause crop losses of up to 80%. Most stinkbugs have 4 generations per year and each generation causes a different type of damage to the nuts.

- The first generation is the spring generation (August to September), and occurs during or after flowering. This generation can cause extensive flower and/or fruit drop of small macadamia fruit.

- The second generation is the summer generation (December). Damage occurs during fruit development or just before the fruit reaches mature size. Once the fruit has reached mature size, it remains on the tree even after stinkbugs have fed on it. When harvesting, these nuts will have large, sunken lesions on the kernels.

- The third generation, the autumn generation (February to March), is normally the largest. This generation feeds on the nuts before and during harvest. Although it causes lesions on the nut kernel, no fruit drop occurs.

- The fourth generation stinkbugs (winter) do not normally cause problems because most nuts have been harvested and stinkbugs are not very active during this season. The damage evident at the end of the season (stung nut kernels) is inflicted from December to harvest. The hardness of the shell does not limit stinkbug feeding. Nuts must therefore be protected against stinkbugs throughout the year from flowering until harvest.

And we thought Eldana was a toughie!

The good news is that stinkbugs can be controlled chemically. The shaking method is used to monitor the number of stinkbugs, especially the winter and spring generations when morning temperatures are low. Ten trees must be chosen weekly at random per control unit/block (a unit is not larger than 5 ha). Place some white plastic roof sheeting around the base of the tree and shake the lower branches. Count the stinkbugs that have fallen down. Trees must be shaken before the temperature exceeds 18 °C, otherwise the stinkbugs will fly away when the branches are shaken. The economic threshold value (in other words the level at which economic damage to harvest occurs) for this method is an average of 0,7 stinkbugs per tree.

Whenever chemical control is necessary pesticides should be applied judiciously. At present cypermethrin and endosulfan are the only active ingredients registered for use against stinkbugs, although I have heard that the latter one has been taken off the shelves.

Problem #2: Phytophthora root rot

This disease usually occurs as a result of mechanical damage causing injury. These areas usually become infected. Trees suffering some kind of stress such as drought conditions may also get the disease.

Problem #3: Nut borer

Nut borer is the common name for the larvae of 4 types of moths that can either burrow into the green husks of macadamia nuts or feed on the kernels. The damage can easily be recognised, but the moths are small and inconspicuous and seldom seen in an orchard.

An infested nut can be recognised by a small hole in the husk which is surrounded by excreta.

Affected nuts, especially young developing nuts, usually drop as a result of damage to the husks.

Susceptibility to attack by moth larvae differs among cultivars because of hardness and thickness of the shell. I had heard that no insecticide is at present registered against nut borer but, in the Madumbi Sustainable Agriculture article on their products for macs, I see that they have two products for the nut borers – go to their advert above and click through to the link for more information.

HARVESTING

Macadamia nuts drop from trees when they are mature and are then collected from the ground. Some cultivars respond well when a herbicide is used to facilitate ripening, much like in sugarcane.

The area underneath the trees must be clear. Grass, old leaves, branches and other debris must be removed. The nuts must be collected regularly, at least once a week. Nuts remaining under the trees for too long lose quality and are susceptible to damage by mould, rats and other rodents.

During the main harvesting period the branches may be shaken to loosen the nuts. Never pick immature nuts. Once harvested, the must must be dehusked within 24 hours and dried.

Credit to Summerland House Farm for this graphic

Credit to Summerland House Farm for this graphic

STORAGE

The hard, undamaged shells offer adequate protection against insects during storage. The kernels of shelled nuts are, however, susceptible to infestation. Because insects can infest stored nuts, the necessary preventive precautions should be taken. A reasonable degree of insect control is possible if packhouses and storage areas are kept absolutely clean. If nuts are to be stored for any length of time, it would be best to store them unshelled. Before they are stored, any cracked or broken nuts should be removed because cracks in the shell will provide access to insects.

Because shelled nuts are susceptible to insect damage, they can only be successfully kept in cold storage. The nuts should be packed into cartons as soon as possible after shelling. They can then immediately be placed in a cold store at 0 to 4 °C. Cold storage prevents fungal growth and rancidity. This method is also recommended for the long-term storage of unshelled nuts.

SHELLING

For successful shelling, the nuts should be dried to a moisture content of about 1,5 % to ensure that kernels shrink away from the shells. Therefore, nuts should be dried before shelling. The final drying takes place in large containers through which hot air is circulated.

The macadamia nut has a very hard shell, but is easily cracked mechanically between rotating steel rollers. A nutcracker or shelling machine works on the principle that nuts are cracked between a rotating steel roller and a fixed plate. The distance between the roller and the plate is adjustable according to the grading size of the nuts. The kernels of the nuts that have been properly dried, drop from the shells when the nuts are cracked.

RETURNS

What to expect from your investment, ie: what do macs look like in the bank account?

| Year | Cost | Yield per tree (kgs)

Nut in Shell |

Yield per hectare (kgs)

(av 312 trees per hectare) |

Price per kg

(conservative) |

Income per hectare | Net position |

| 1 | 100 000 | 0 | 0 | R 60 | 0 | · 100 000 |

| 2 | 25 000 | 0 | 0 | R 60 | 0 | · 125 000 |

| 3 | 25 000 | 0 | 0 | R 60 | 0 | · 150 000 |

| 4 | 25 000 | 0 | 0 | R 60 | 0 | · 175 000 |

| 5 | 25 000 | 0.9 | 300 | R 60 | 18 000 | · 182 000 |

| 6 | 25 000 | 1.92 | 600 | R 60 | 36 000 | · 171 000 |

| 7 | 25 000 | 3.85 | 1200 | R 60 | 72 000 | · 124 000 |

| 8 | 25 000 | 5.8 | 1800 | R 60 | 108 000 | · 41 000 |

| 9 | 25 000 | 7.7 | 2400 | R 60 | 144 000 | + 78 000 |

| 10 | 25 000 | 9.6 | 3000 | R 60 | 180 000 | + 233 000 |

| 11 | 25 000 | 10.3 | 3200 | R 60 | 192 000 | + 400 000 |

| 12-15 | 25 000 | 11.2 – 12.8 | 3500 – 4000 | R 60 | 210 000 – 240 000 | + 585 000 – 615 000 |

Please understand that these are averages with SO MANY factors that could affect the figures either way. Yields vary with location, season, variety and level of management. The figures also assume that trees are pruned to maintain machinery access, light penetration and spray penetration. Note that in orchards spaced more closely, yields may reach the peak per hectare figures earlier than indicated. However, yields may then decline without pruning and good management. With good management, yields per hectare for mature trees are generally similar for all spacings.

LONG TERM

It’s clear from the table above that macadamias are a long-term investment, unlikely to produce within the first seven years, with your return on investment only being appreciated in year 9. As I pay more attention to this mac market, I am learning that these figures are conservative, with many farms, including the trials being done in Komatipoort, yielding crops in year TWO!!

The returns are unarguably impressive and you don’t have to replant for at least 40 years – it’s easy to see why so many people are going (growing) nuts!

But, is South Africa’s macadamia industry sustainable?

The macadamia industry is small compared with other nut crops. The world’s almond crop, for example, is more than one million tons per year, while the world’s macadamia crop for 2017 was 170 000 tonnes in-shell (just 50 000 tonnes of kernels only).

SA’s 2017 macadamia nut-in-shell crop was 42 000 tonnes, and Australia’s was about 47 500 tonnes.

Twenty years ago, SA was a minor player, and because of that, processing facilities were rudimentary but now, world-class facilities are coming into production. Marketers are also exploring new markets and value-add products as well as conducting extensive research into health benefits of these nuts so that the findings can be used to further stimulate demand.

COMPARISON TABLE

| Macadamias – ESTIMATES | Sugar Cane – ESTIMATES | |

| Age of industry in SA | 56 years | 170 years |

| Size of industry in SA | 53 500 tonnes

19 500 hectares (2,75 t/h) R 3,2 billion |

19 900 000 tonnes of cane

371 662 hectares (53,5t/h) R 5,1 billion |

| Cost to establish one hectare | 100 000 | 35 000 |

| Cost to maintain one hectare | 25 000 / year | 15 000 / year |

| Life span of crop | 40 years | 12 years |

| Income from one tonne | R 75 000 / tonne

R 250 000 / hectare |

R 85 / tonne

R 6 000 / hectare |

I had a healthy debate with myself (yes, I do this often and no, I am not concerned about it) about whether or not to include the comparison table above as the numbers are so subjective and depend on so many variables that their accuracy is highly dubious but, as I prefer to err on the side of boldness than to shy away from contention, I decided that it’s reader value, inaccuracies and all, was worth it. So, please, don’t take this as anything more than a loose guesstimate.

What I do want to deal with is the elephant in the kitchen: if the figures given above are even remotely realistic, why isn’t everyone ripping out their cane and growing macadamias? This is a question I have asked a few cane farmers, and these are the responses I have received:

- It’s never wise to put all your eggs in one basket, which brings us back to the reason we decided to write this article in the first place: DIVERSIFICATION. That doesn’t mean mono-cropping with something else, it means grow a variety of crops. This spreads your risk and gives you independent income streams.

- Sugarcane is an easy, forgiving crop – like an old favourite that never lets you down. New fads will always come and go. Sugarcane is familiar and uncomplicated and there will always be a place for it.

- Reasonably low establishment costs, which is sometimes the only option if capital is small.

- Quick returns. A crop can be turned around in as little as 12 months, and provide ongoing annual income for about 10 years thereafter, depending on how you look after it.

- Economics work on the forces of demand and supply. Macadamias are currently riding a wave of demand exceeding supply but prices will drop when the market is satiated. Sugarcane is currently in a trough and, by the same laws, it will rise again when demand exceeds supply.

- Stick with what you know, do it well and you will be better off in the long run. Beware of the green monster (greed) that entices you to chase money. Only stress and frustration can come from that.

Whilst there is always a counter argument, we cannot deny that these are valid points. And, it brings me back to the reason for this article again: diversify. It might be chickens, a B&B or a mac orchard. But, with the current sugar price, we need to supplement the coffers somehow.

I read that it’s fine to put all your eggs in one basket as long as you can control what happens to that basket. In farming, we know that we are certainly not in control of very much, making it advisable to ‘spread those eggs’.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

I have thoroughly enjoyed getting to know these nutters and would like to acknowledge the following websites for their invaluable assistance:

Samac.org.za

Valleymacs.co.za

nda.agric.za

fin24.com

agrihandbook.co.za

farmersweekly.co.za

ohiwamacadamias.co.nz

outdoordesign.com.au

agrieco.net

summerlandhousefarm.com.au

I have also used photos from my previous farm visits and would like to acknowledge ND Goble Estates, Sunhill Farm and Havelock Farm in this regard. Thank you.