Sometimes I just can’t believe how lucky we are – here I sit, across from, not one, but TWO incredible JAFFs – downloading their invaluable insights for over 8 hours!

JAFF 1 is part of a renown mac farming and processing family and JAFF 2 is an Operations Manager of remarkable pedigree. Together, they make an awesome duo and we are privileged to be here.

| FARM CONTEXT | |

| Date of visit | 13 September 2022 |

| Area | Levubu, Limpopo (Farms in Levubu and Piesanghoek) |

| Soils | Mostly Huttons. Generally 10 to 30% clay content. |

| Rainfall | Piesanghoek: 7-year average is 1250mm. Springfield: 850mm annually. |

| Altitude | 750m – 1300m |

| Distance from the coast | Over 400kms |

| Temperature range | Record high – 43°C (Jan). Average high 31°C (Nov) Record low – 3°C (June). Average low 9°C (June) |

| Varieties | Fuerte, Hass, Ryan, Gwen, Lamb Hass, Pinkertons, Edranol, Reeds. |

| Hectares of Avos | 182.15 ha (146.24 ha in production). |

| Diversification | Avos: Nursery, Packhouse and Partners in an Export Business. Macs: 267.19 ha. Also Nursery and Processing and Marketing Company. Pecans: 79.01 ha. Shareholders in a Processing Company. Timber: 850ha (Gum) |

We’re going to cover this extensive story in two parts:

PART 1

- Getting to know the JAFFs

- Avo history and getting started

- Markets

- Development Planning

- Land Prep

- Nursery

- Planting

- Soil Health and Nutrition

PART 2

- Orchard Regeneration

- Pruning

- Irrigated and Dry-land orchards

- Pest Management

- Pollination

- Harvesting

- Export

PART 1

Both JAFFs are young and fairly new at the reins of this large, family-owned operation. JAFF 1’s Dad started as a farm manager for an old agric business in the area that did mostly timber. In 1983 Mondi bought that company out but didn’t really want the macs, avos & pecans that were part of the package. JAFF 1’s Dad was also a little unsure about his future with the change of ownership and put in a bold offer to buy the parts of the operation that didn’t fit in to Mondi’s portfolio. And the rest (will be) history as soon as we write it down! So began the operation we investigate today. Over the years, it has undergone significant expansion.

The big story here today is about TRANSITION, where new entrants into the business bring enthusiasm and modern farming techniques but can lean on the experience of a long-standing, successful farmer. We know that many farming enterprises are “hereditary” and that this topic is a burning one for most of our readers. There are so many new, fresh ideas around technology and development, brought into the fold by the younger generation, it can be a challenging phase as the old guard gives way (or not) to ideas and methodologies that are yet to be proven. It is with great respect that we listen to how this transition is successfully playing out in this business. The combination of experience, enthusiasm, the use of new technologies, and with the support of a fantastic team consisting of excellent Farm and Assistant Farm Managers, has made the transition effective. It isn’t always easy; but nothing worthwhile is. So, top up your coffee cup and sit with us a while …

GET TO KNOW JAFF 1

Despite the fact that he was born at the local (Elim) hospital (as the crow flies it’s not even 20kms away) and grew up on these farms, JAFF has picked up some mileage between then and now. He went to high school at Michaelhouse, and then chose to do a PPE degree (Politics, Philosophy, Economics) – no, we don’t know why! – and then managed a local farmer’s (not his) mac operation for 4 years. It was here that his love for agriculture really developed. He then left our shores for some international education; at the Royal Agricultural University in the UK where he did an MBA in Global Food Business. From there he went on to work for a UK Fresh Produce importer managing their chilli’s, seasonal and baby vegetables into Tesco’s. However, his love for Africa and the farm always remained, and after 7 years, he returned home, to the family business. Here he spent time in the trenches, getting to know his way around all aspects of the organisation, starting off in nut procurement and processing. He then joined his father in managing the expanding farming operations, with his dad gradually slowing down, he knew to achieve their goals of being a leading farming organisation, help was needed. But not just any help; he wanted the BEST and someone who complimented the farm’s future strategy …

ENTER JAFF 2

JAFF 2 grew up in the Polokwane, Tzaneen area, went to Pretoria Boys and did an undergrad in Environmental Science at Stellenbosch, majoring in Soil Science and fluvial systems (yes – I had to Google that … it’s all about water ). He then continued with a post grad at TUKS – in Environmental Science. JAFF was headed for the mines but, when he got a call offering him a farm management position, the bush lover in him changed lanes.

It was at this job that the two JAFFs first met but their paths diverged from there with JAFF 2 moving on to the Halls Group about 3,5 years later. From there, he entered one of his greatest growth experiences as he was appointed as the agricultural manager at a Crookes Bros operation in Northern Mozam. The 500 ha of macs in an extremely remote area certainly taught him independence. Under the mentorship of the experienced MD, he was involved in all management aspects from growing to marketing and all the logistical challenges in between. The climate and soils were perfect, and he had 6-year-old trees producing 4,5 t/ha. The top SKR results on A4s was 50% .

140ha were under gravity irrigation, sustained by weirs built in the vicinity where the Portuguese had built weirs 100 years before. “It was a very interesting project,” JAFF understates, “I got married while I was up there and, when this SA opportunity came up, with a fantastic company, it was enough to pull me back home.” He’s been here for 2 years now.

OKAY – TIME TO GET INTO THE FARMING BUT WHICH CROP DO WE DO?

Again we find ourselves teetering on the cusp … should we do macs or avos? This farm is successful in both … JAFF tries to guide the decision; “There are not too many places in SA better than Piesanghoek to grow avos – the soil, rainfall and altitude are all perfect. Macs though … mmm – we have great soils but can’t compete with KZN in terms of climate. We do have more macs than avos though …” In the end we decide to stay true to TropicalBytes’ ‘new’ crop and cover avos. Although, if something interesting on macs comes up, we won’t be able to ignore it!

SOME AVO HISTORY

I’ve been under the impression that avos are an OLD crop but, I learn today, that, compared to apples, pears and citrus, they’re not that old. Actually, closer to macs than I imagined.

The main crops in this area were traditionally citrus, bananas and veg. Until the 1950s, when black spot became too challenging – the (ever resourceful) farmers tried avos. This kicked off the first large commercial plantings. Given that macadamias were being ‘test driven’ in the 60s already, they’re in the same ‘generation’.

JAFF’s family put up their avocado packhouse in 1982 and their first macadamia processing facility started production in 1991, although they had been supplying SAD before that. Macs have had a bit more of a tumultuous economic journey. Avos are only now experiencing their first real market ‘pressure’.

Scale is often a difficult thing to capture in photographs, so I was grateful that JAFF was hidden/not hidden in this photo (see how small he is next to this seemingly ‘normal’ size tree!) The farm we are about to explore is LARGE – both in terms of hectares, scope and age range of the trees. Keep this scale in mind when you look at the pics where I didn’t manage to get a sneaky of the JAFFs.

CULTIVAR MARKET selection

We’re so used to macs and starting the discussion off with Nurseries and Cultivar selection that it’s taking a while to remember that avo farmers do it differently. We do believe that the recent shift in the mac markets has taught mac farmers to take some notes though.

So, the JAFFs first assess the market; which, for them, is predominantly European. Other countries, bigger than SA but playing in the same arena, are: Mexico (but they eat most of their own produce), Peru (we meet them head on in the market), Chile, Columbia, and at stages Spain, Israel and Morocco … competing against any of them can be pointless as some governments subsidise their growers … quality and finding a gap in the market is the key to success.

Finding NEW markets is the ultimate goal, like the USA … at one point in 2022, the price for a carton in the USA was $27 and, in Europe, it was €5 – in the SAME week! Supplying the US is all about trade agreements – and trade agreements can only be negotiated by government officials.

With the highly dynamic nature of markets, knowing exactly what to plant involves some long-term strategic thinking (aka guessing ) eg: if the Chinese/US market opens up, what do they like eating? Right now, the market is Europe and they like Hass so that’s what’s being planted! Locally, Levubu does well with early season Fuerte so JAFFs also grow for this. (It’s only a couple of weeks though until the rest of the country comes in and this price then drops quite quickly).

So, the strategy here is:

- Mid-Feb to mid-April – Early season Fuerte for the local and export market.

- Mid-April to July – Hass for export.

- Early August – Ryan.

- Late August – Gwen, Pinkerton & Edranol.

- September – Lamb Hass.

- October – Reed into the local market.

The aim is to stretch the season over as long a period as possible so that the peaks and dips are levelled out over the year, “However we do make a big push to target early Fuerte in the local market and earlier Hass into Europe,” adds JAFF. Aug – Oct is considered ‘late season’ and fetches better prices so it makes sense to stretch these avos as late as possible.

Another consideration in the ‘big picture’ is that a packhouse is a huge investment – you can’t justify having one that runs for only 2 months of the year (and concentrate all your production into that) – stretching your season will also reduce your marketing risk , it allows a smaller packhouse to operate for a longer period, however it could be limiting when targeting the price peaks in the season.

Looking to the future, current developments are predominantly Hass, along with a few later season varieties. Playing into the strategy of stretching the season, they are also planting at altitude (orchards at 750m, 800m, 900m, 950m, 1000m, 1300m) – the higher they are, the later in the season they’ll be ready.

If you’re raising an eyebrow rest assured, they’ve done trials and there are no maturity issues, in fact, it all looks very promising. It’s mostly old timber land but the soils are excellent; mostly Huttons with some Oakleaf and Glen Rosas. The Piesanghoek farms are quite steep but the JAFFs say that just helps drainage. “The climate is similar to Tzaneen – great for avos. Not as ideal for macs because the humidity is less which (they say) means the shells are thicker.” To get around this, on the Piesanghoek mac developments, they are planting more hybrids like A4 and A16 which have thinner shells and larger kernels. “Levubu gets hot, dry winds in from the Kalahari, especially in flowering times; we believe this stress and lack of moisture also contributes to the thicker shells.”

So, JAFFs’ advice is that once you’ve assessed the markets and decided what it is you want to grow, you then get the soil scientists out. They suggest this happens 6 months to a year before the excavators arrive to remove whatever is in the soil currently; like old uneconomical orchards, timber etc.

DEVELOPMENT PLANNING

Yup – that’s a new headline for us. But it’s a critical phase – the foundation on which the whole development rests. Now that we’ve been introduced to it, we see it’s kinda crazy not to do it …

STEP 1: Soil scientists come in and grid, ready for detailed, precision analysis.

STEP 2: The soil is analysed, and the zones mapped. Soil zones = management zones.

STEP 3: Full development design is done including:

- soil preparation recommendation (i.e., tillage recommendations),

- drainage (sub surface and surface water management and erosion control),

- block layouts (including row direction, plant spacing, roads, probe sites (2 per hectare), management units)

- Cultivar and Rootstock selections – through consultation and in line with the farms strategy.

All this costs R1000 per hectare. “We’ve got one chance to do development properly and believe it’s worth the investment,” says JAFF. He also says that most large corporate farming companies include this cost as mandatory for all new developments. If precision farming is the aim then accuracy is key.

This development plan (which includes soil types and their unique water holding capacities) is then the base for the irrigation plan. It also affects the nutrition programme because different soils have different nutrient storage factors.

This is one of the new avo developments. It was a purchased macadamia orchard that was B.E.R. (beyond economical repair) – seedlings that had been pruned poorly. JAFF explains that macs don’t come back well from very harsh pruning like avos do.

As they are trying to separate the macs and avos (for pest management), they’re trying to keep the macs lower down where they do better than the avos, in the cool valleys. Avos can get cold damage if the temperatures go too low. The irrigation plan for this new development is to pump, from the river, up to a reservoir and gravity feed from there.

LAND PREP

Now that the plan is finalised on paper, it’s time to bring in the heavy, yellow metal. The methodologies to guide this process are also covered in the development plan eg: which direction the first rip should be and which direction the second rip should be; obviously depth and equipment to be used is also detailed. This is important because it affects subsoil drainage and creates little ‘channels’ for subsoil water to move, or not move, as is the requirement.

JAFF used an excavator to remove trees and stumps in this development, currently underway.

The old macadamia trees are being burnt. After this a tractor with a special implement designed to clear the sticks and small obstacles left in the field will come in so that liming and P applications can be done smoothly after that.

Once the old trees are out of the way, they start liming. JAFF says, “This is a hot topic because farmers generally don’t want to go over 4 to 5 t/ha but pHs, especially in old pine or mac blocks, can be as low as 3,6.” He goes on to say that they’ve used up to 11t/ha, calcitic lime, and have not seen any negative repercussions from the perceived ‘heavy handedness’. JAFF provides exactly what the soil is short of, exactly where it is short; there’s no ‘blanket’ applications.

Depending on magnesium and calcium levels, they use either calcitic or dolomitic lime (read more in QUIPS Edition 18 link). JAFF emphasises the importance of making sure spreaders are accurately calibrated.

After lime, phosphorous is applied. They aim for 30 ppm in the soil in avos (Macs get slightly less; about 20 ppm). “Avos are not as good as macs when it comes to scavenging phosphorous,” he reminds us. Phosphorous is also applied with the lime spreader and averaged about 0,5 to 0,75 t/ha on this latest development. They use double supers (20% P) which cuts down the volume required.

Required lime and phosphorous has been applied. The markers help workers on the ground navigate between what they see on the maps (development plan) and where they are.

Once the lime and phosphorous is down, it is ripped into the soil, according to the development plan directions, depth etc. It’s usually a deep (80cm to 1m), 3-tine, downhill rip first with the cross ripping done at 40° to 45°, as per the planting rows. The entire field is cross ripped, not just the row, this loosens the soil even further, alleviating most soil physical limitations which could affect root growth. This method also allows for easier ridge construction. Once the cross rip is complete, the area is disced, which reduces soil clumps (not wanted in the ridge) and mixes ameliorants into the soil even further.

Then the surveyors come in and peg key points so that the roads and ridges/terraces can be built accurately, as per the development plan. The bulldozers then push the lines and roll the ridge up to about 50/60cm in height. They will settle down by about 10cm so the final ridge is approx. 40cm high, 2,5m wide at the bottom and 2m at the top.

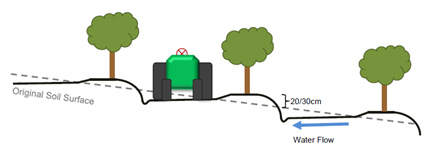

On steeper slopes, pseudo terraces are constructed, where soil is levelled between planting rows and moved towards adjacent trees to create a 20-30 cm ridge, above the levelled tree lane.

Pseudo ridges recently prepared in JAFFs new developments.

The soils here (on this farm) are generally 15 to 20% clay content – which means water retention is good BUT, it can be too good if the rainfall is high like the 1800mm they had in Piesanghoek in 2021. “In rainy years, you can have 3000mm on those farms!” Although the 7-year average is 1250mm.

Spectacular soils, expertly worked and ready to receive the new trees.

Spacing on all new avo developments is 8m x 5m.

Cover crops are planted in Sept/Oct. They throw seed by hand, on to the interrows only, leaving the ridges (top and sides) bare. The seed is then disced into the ground. The cover crop mix is made up of Pearl Millet (10 kgs/ha), Sorghum (12kgs/ha), Sunflower (4 kgs/ha) and Cow Peas (14 kg/ha).

Interrows allowed to grow but will be slashed soon because trees are young and require light and air.

Avos are usually planted at the same time as the cover crop (Aug/Sept), depending on when rain is coming. If the weather is wet and cool, they also plant in Jan/Feb.

Avo trees (grafted seedlings) come from JAFFs’ own nursery and are hardened off before they go out into the field. Part of this hardening off involves spraying silicates 2 to 3 weeks before planting and to stand the young trees outside. Both these activities help to harden the leaves. Avo leaves are softer than macs and need the added resilience. Clonal avo trees are outsourced.

NURSERY

An integral theme in this operation is vertical integration, both downstream and in the supply chain. In line with this, they have invested in nursery facilities and are making their own trees.

They are not yet venturing into clonal rootstock and everything is grafted seedlings; Reed, Edranol, Velvick and Duke are the preferred root stocks currently. In an effort to refine and narrow the options they are deliberately splitting up root stocks and using 4 different varieties in the new developments, including clonal plantings (dusa rootstocks). They will use the results from these orchards to refine their selections going forward.

By skipping the clonal root step, they can get a tree ready to plant out in 12 months, however they intend to develop a clonal nursery in the next few years.

Sunblotch testing is currently a big discussion item and the testing seems to be a challenge … As a result, JAFFs’ nursery test thoroughly and continuously and has a zero tolerance.

Although the commercial life of an avo tree is estimated to be around 25 to 28 years, the oldest trees on these farms are 58 years old. They are still yielding handsomely, especially after the regeneration efforts. JAFF says that the challenge with an old orchard is that it tends to have gaps which affects yield per hectare … so farmers need to be careful that they assess how the individual trees are yielding before ripping them out. Right now, the focus here is on new developments but they will come back to these old orchards and re-establish, on a 30-year rotation.

When assessing an avo tree in the nursery, JAFF advises that you remove the bag and inspect the root system – it must be vigorous and white with a strong, straight tap root. “Don’t accept any black or dead roots as planting a tree with phytophthora from the nursery is not acceptable.” He says that avos are not as sensitive as macs when it comes to j-rooting but here, there’s zero chance as they plant seeds straight into the bags, thereby eliminating any double handling which is where root damage often happens.

JAFF was very open in sharing some examples of roots that won’t make it through this nursery – culling is ruthless with only the best making it through to the orchard. The one on the left’s journey ends here as the root growth is not extensive or strong enough. The one on the right is a good specimen.

5 months after placing the seed in the bag, it’s ready for grafting. Grafts take much easier in avos than in macs and you can usually graft throughout the year. Avos are such promiscuous babies that they will sometimes even produce flower buds in the graft so it is important to pause grafting in the flowering season.

Notice all the flower buds on the grafts in the group on the left (Grafted in June). The batch straight ahead was done later and the grafts are producing leaves.

Although this graft has taken and the roots may be strong, the graft point is not perfect and this tree won’t be going any further.

Once the trees are 1 to 1,2m high, they are ready to plant.

Nursery Care:

- They take a preventative stance against Phytophthora, especially in rainy season, by using drenches to clean and regenerate (Trichodermas) the planting medium.

- They stimulate growth by using kelp on all young trees; both macs and avos.

- A+ graduates only. Anything that leaves the nursery, destined for the orchard, has to be 100% healthy; no drooping leaves, no black roots, slim stems only, perfect compatibility at the graft point.

PLANTING

The orchard is pegged out properly with spacing done accurately. A hole, ‘quite a bit bigger’ than the bag, is dug so that all the surrounding soil (underneath and sides) is soft and easy for the roots to penetrate.

The detailed planting process is as follows:

- Water-retaining gel crystals are premixed at 1 kg/100 l, mixed for 30 mins and settled for 15 mins, until a gel is formed. On planting, 2 L of this gel is mixed with soil and distributed evenly throughout the planting hole.

- Lose soil (mixed with some gel) is then placed at the bottom of the planting hole.

- The planting bag, is then cut at the bottom of the bag (not disturbing plant roots), a slit made on the side of the bag and the tree is placed into the hole, where the nursery soil level meets the planting hole soil level (not to be planted too deep or too shallow).

- The bag is then fully removed and lose soil (mixed with gel) is place around the tree up until 10 cm below the plant hole soil level.

- A slow release NPK+ Trace element fertilizer is then applied at 200 g /plant, mixed into the loose soil, and placed in the planting hole at 5-10 cm from the stem, at a depth of 0-10 cm.

- A fungicide is mixed at 375 g/ 100 L , this mixture is then drenched into the planting hole by applying 5 l of each mix onto the planting soil (ensuring a thorough drench is achieved).

- The final, unmixed soil is then placed to fill up the remainder of the planting hole.

- The plant is firmly staked in an upright position, with reference to the planting line it is in

- The soil is then slightly compacted by hand.

- A wide basin is constructed around the tree.

- Once the basin is constructed, water is gently applied into the planting hole, fully filling the hole (about 20-40l). Removing all air pockets.

- 1 bucket of Mulch (husk/chip mix) is then applied per tree, with a gap left surrounding the stem.

- Buck protection Is installed either on an individual plant basis, or surrounding the entire orchard.

1 to 2 weeks later they come through with trichodermas and this continues, once a month, for 3 months. The trichodermas are mixed with molasses and kelp; the molasses feeds the bacteria and the kelp stimulates root growth.

This 17ha was a neat rectangle and could be closed along the perimeter. The trees need to be 2 to 3 years old before the netting can be removed.

In the young orchards, they clean up on the ridge but allow weeds and natural vegetation to grow freely in the interrow. In the older orchards, the ‘freedom’ extends onto the ridges but there is a big annual clean up in December when some maintenance is done so that people and equipment can access the orchards effectively.

SOIL HEALTH AND NUTRITION

JAFF starts this conversation off by saying, “If your soil isn’t happy, your trees will never be happy.” So, what does ‘happy’ soil look like? JAFF believes it includes a decent amount of organic matter. “Thankfully, avos self-mulch incredibly well and we don’t need to supplement the older orchards at all but we do make sure that the younger ones get decent helpings of supplementary mulch.”

Something that’s always concerned us is the potential damage caused to soil life, when the copper spray drips onto the soil; it’s a fungicide after all and the detrimental impact on soil-based life is inevitable. JAFF is equally concerned but hasn’t yet found a solution. They spray copper on the green skin varieties 5 times per season. He does point out, though that, with the thick layer of leaves covering the soil in the drip zone, that the damage is less than we imagine.

Soil and leaf analyses are done every year, in March, when nutritional programs are set up, including ameliorant programs (by this JAFF means calcitic lime or dolomitic lime) which are added once a year.

JAFF is gleaning immense value from a data platform that takes your farm’s information (location, soil, cultivar, spacing, canopy size, application rates etc) together with norms it has established from other farmers feeding in their data. It then factors in crop removal rates and gives advice on your nutrition programme and how it aligns with norms. AI (Artificial Intelligence, not insemination ) really is touching every sphere of our lives, even when you’ve chosen a ‘least likely’ career like farming!!

JAFF uses semi-organic fertilisers on all avos and the dryland macs. Semi-organics worked out to be the most cost-effective way to supply the nutrients, as opposed to straights. They then supplement with extras like potassium sulphate because there’s often insufficient in the blend. The visual assessment on shortages is done around August and supplementation done as required. In November they’ll reassess the set and adjust the rest of the year’s programme, based on what the trees are actually carrying.

The annual requirement of fertilisers is split over 6 applications, starting in April and are applied as follows: April 25 %, July 10%, Aug 20%, Oct 15 %, Dec 20% and Feb 10%, although the exact time of the applications depends on the phenological cycle of the trees. Nitrogen is concentrated into the earlier months with less being supplied later in the season. This was a learning for us; that too much nitrogen later in the growing season, causes grey pulp which is further exacerbated if there’s too little calcium getting to the fruit. Beside this late season requirement, calcium also needs to be available to the tree well in time for fruit set (applied 6-8 weeks before set) so they get this in early and top up throughout the growing season.

JAFF likes to get the traces (like borons and zincs) applied as foliar sprays, before fruit set. Some traces are also included in the blends or applied as straights at a similar time. He explains that avos need similar nutrients as macs; for similar things that macs need them for, eg: nitrogen for growth, boron and zinc for flowering, calcium for cell walls etc.

JAFF shows us how Boron deficiency shows up on an avo leaf – the small holes (shotgun holes). Hope you’re taking notes – this is a great QUIPS question – ah – too late; we already used it!

All semi-organics are applied by hand, underneath the tree canopy area, with chicken litter as a carrier.

JAFFs’ nutrition programme is designed to grow fruit, not trees, and is therefore limited in nitrogen (which boosts vegetative growth) but is generous with nutrients that boost fruit eg: Molybdenum which isn’t rated very highly by most farmers but JAFF believes it is vital to achieving overall balance. (And he’s basically a Soil Scientist so let’s take his word for it and plan in a full study on molybdenum asap.)

Not managing to shake our fascination with feeding trees through their leaves, we spent more time on the foliar feed programme. JAFFs explain that the trees do absorb through their leaves and so it makes sense to use the ‘opening’. Their programme starts at budding time with a cocktail of boron, zinc and kelp. 3 to 4 weeks later, they spray again, just before the flowers start opening. And again when fruit has set but is not quite pigeon egg size (don’t worry, we got you – pigeon eggs are 3 to 4 cm long). This spray includes calcium and kelp.

We’ve been hearing a lot about kelp lately … the fact that it grows exceptionally fast lead scientists to try and unlock and access the hormone responsible for this rapid growth. The answer; cytokinin. “Feeding this to our orchards has shown impressive results,” says JAFFs. And it is purported to have the additional ability to signal/encourage/instruct plants to take up other available nutrients. From what we hear, the research data is supporting the claims.

JAFF is very generous and continues to share his invaluable learnings on nutrition; if Zinc levels were low when they did annual testing, they apply another dose of this element in January – together with kelp, on avos’ soft flush. Kelp applications end up being applied 3 to 4 times annually.

They’re certainly getting a lot right – one Hass block did 26,5t/ha last year (23 years old planted at 7m x 3m. Pruned heavily just before this bumper crop). While this was a wonderful surprise, it was only fed to produce 15t/ha and they now need to pay extra attention, and nutrition, to avoid an ‘off-year’. Of course, we want to know why this block excelled but the JAFFs can’t isolate the reason, “We are doing lots of different things and, while it is producing results, we’re not entirely sure exactly which input is responsible for the results. Perhaps it’s the combination! One thing with farming is that a lot of small things can make a big difference; it’s very seldom one thing.”

JAFF does advise that, if you see your trees exceeding their target, try to take the crop off as early as possible so that they have longer to recover before the next season. They misjudged the size of the harvest on this block and didn’t get it off early, which will further impact its ability to ‘repeat the performance’ next year. There should be no more than a 2 ton variances between seasons; more than that could indicate an alternate bearing issue.

This operation produced 900 tonnes of Hass last season and similar volumes of Fuerte. That’s 400 tonnes more than the previous average. While the JAFFs know they’ve worked hard to make improvements he also knows they were very lucky, “Sometimes, you can do everything right and then inclement weather impacts your results negatively … so, then … how much of the success is a result of what we did and how much is just the weather?” The humility is wonderful but I encourage you to keep reading – these JAFFs are doing some amazing things and we have no doubt that the weather is a limited factor. But still JAFF insists, “Last year there was 10 days of badly-timed, uncharacteristically wet weather and all the Beaumonts got a fungus – even with our preventative fungal sprays – there was a low Beaumont crop!” Not ones to lay down and accept poor performances, he adds, “We have pruned these macs heavily, and opened lines, to limit the chances of this happening again!”

Besides all this nutritional care, JAFF administers one bucket of kraal manure to sick trees. And there’s a lot more wonderful soil-wisdom to come, under the ORCHARD REGENEREATION discussion.

JAFF advises that, because chloride-based fertilisers can result in a salt build up in the soil, they’ve moved over to sulphate-based products now. He concedes that it is more expensive but avos absorb potassium far better from potassium sulphate than from potassium chloride, justifying the switch.

A fresh load of kraal manure ready to feed the soil around new trees and first aiders.

And that’s where we’re going to break for now. Be sure to pick up Part 2 of this story, same time next month.

PART 2

- Orchard Regeneration

- Pruning

- Irrigated and Dry-land orchards

- Pest

- Pollination

- Harvesting

- Export