Some interview opportunities arrive in unexpected ways; this was one of those. A friend suggested someone he knew as a possible JAFF; but this friend is a doctor, not a farmer, so “how does he know he’s a fantastic farmer?” was the foremost question in my mind. But, the farm is big, successful and has been around for generations so, I figured “how bad can he be?”

And so, a few days into Spring, I was privileged to be hosted at this magnificent farm by this humble and down-to-earth farmer who was also not sure why I was interviewing him! 😂 Sometimes we just need to go with the flow and be open. Thankfully for us, JAFF was, and he was gracious enough to share his knowledge, his lunch table, and his journey. And he’s a REMARKABLE farmer!

JAFF was raised on this farm. The family comes from German heritage who brought incredible value to our farming communities when they arrived as missionaries about 150 years ago. Sadly, at the time of my visit, JAFF was considering emigrating to Australia and so we may lose another brilliant farmer to that continent where they can’t play rugby, or cricket, or breakdance very well. 🤣

Moving along – let’s introduce the FARM:

| FARM CONTEXT | |

| Date of visit | 12 September 2024 |

| Area | Kranskop |

| Soils | Soils: nice areas of high organic matter with a few pockets of sandstone. A few south facing aspects tend to be sandier. |

| Rainfall | 1000mm annually |

| Altitude | 1000m |

| Humidity | 60-70% |

| Temperature range | Moderate and temperate.

Slightly cooler than most areas in KZN because of the altitude. Average low of 7,5°C. Average high of 26°C. |

| Cultivars | Lamb Hass, Hass, Reed, Pinkerton

About 50ha of Hass | 20 ha of Lamb Hass & Reed | 30ha Pinkerton |

| Extent & Diversification | Total farm is 388 hectares.

The crops include 50ha macs, 100 ha avos and 150ha wattle. The balance is valleys and open areas. |

Although JAFF grows both macs and avos (and wattles), I tried to focus on the avos primarily. But please forgive my ‘soft spot’ for macs and the odd deviation into some interesting points around JAFF’s macadamia farming.

JAFF’s Dad was a cane farmer who, in the 1990s, wanted to expand his operation. As we know, viability in cane farming is closely related to volume and that requires more land. There was precious little of that around this area, at that time, and so he started considering alternative, higher value crop options. He decided on avos and the first 10 hectares of Pinkertons were planted in 1997. The farm now hosts 100 hectares of avos.

JAFF Snr had initially decided against macs because of how high the farm is (1000m) and he had been led to believe that this would most certainly result in small kernels, thick shells and poor results. But the nurseryman supplying their avo trees haled from Nelspruit and he advised that they challenge that belief as there were many farmers in Nelspruit, planting above 800m, who were getting good results. This encouraged them to reconsider and look more closely at the couple, random mac trees already growing on the farm. Ultimately, after some typically German, intensive research, they decided it was worth replacing the remaining cane with macs. It didn’t make sense to continue with only 50 hectares of sugar and, even if they only managed half the KZN macadamia industry average in quantity, with a lower quality, they’d still do better than the cane. And so, in the early 2000s, the cane made way for 12000 mac trees which were all planted in one year! Nothing half-hearted about these farmers! 🤩

I know, I know, I’m getting to the avos … let me just wrap up on the macs:

They’re all dryland. The cultivars are A4, 695, Nelmak 2 and 816. Even the 816s are doing well without irrigation and at this altitude where humidity can drop as low as 10%. These 816 ‘fuss-pots’ were planted in 2015 and last season, at just 9 years old, they produced 130 tonnes off 50 hectares (that’s 2,6 tonnes per hectare) – not bad for young, unirrigated trees. “And the quality is great in terms of sound kernel,” adds JAFF. “My goal is a 4t/ha average for the macs which may sound low to some but, remember they’re dryland and we’re in a marginal climatic area as it is when it comes to this crop.”

JAFF’s neat and tidy mac orchards.

WHEN THE NON-PERISHABLE NATURE OF MACS BECAME A DISADVANTAGE

I was interested to hear ‘the other side of the perishability coin’ from JAFF. I’ve always thought that the highly perishable nature of avos was an obvious disadvantage BUT … last season the mac returns plummeted by about 45% on the previous season because of their non-perishability. The 2022 crop was not fully sold and this impacted supply, forcing prices down in 2023.

Because avos can’t be stored for more than about 5 weeks, ‘gluts’ clear pretty quickly allowing prices to recover quickly.

AND WHO IS JAFF, AS A FARMER? (FARMER CONTEXT)

First off, JAFF is a man of God; he trusts the journey that’s been mapped for him and finds peace in the fact that he’s not in control, especially as a farmer. He accepts the good with the bad without taking on either the accolades or admonishments that come with good or poor results. Which doesn’t mean he’s hands-off … “I plan very carefully but fully accept that everything may not go according to my plan,” says JAFF.

JAFF chose to forego tertiary studies and get into full-time farming straight after school. Up until 18 months ago, he was farming with his brother.

Rather than being a fanatic on the environmental spectrum, JAFF aims to balance economic viability and environmentally responsible farming. He works hard to make FULLY informed decisions that consider the sustainability of the environment AND of his business.

When it’s hard to put a price to something, JAFF errs on the side of the environment eg: mulching, which is done without being able to gauge the exact cost or benefit.

They do use herbicides, pesticides and chemical fertilisers here but always cautiously. The goal is to start incorporating biological farming practices in tandem but because it is challenging to run these two approaches alongside each other, I dove a little deeper; “We would like to improve soil health through natural support,” clarifies JAFF, “by equipping the soil to improve its health by adding ‘soil life’ (bacteria etc).” Although they’re not currently supplementing, JAFF believes that a healthy tree will defend itself better than an unhealthy one and would like to harness that natural benefit.

AVOS

Finally, we turn to the avos … “They do really well at this altitude,” says JAFF thankfully, “the cooler, more temperate climate means that we harvest about 1 month later than the rest of the industry.” This translates into filling valuable gaps ie: landing fruit in Europe when there is higher demand. Peru’s supply has flooded some of this late window but it’s still better than the main window where prices are lower.

CULTIVARS

Of the 100 hectares of avos on this farm, about 50% are Hass and all new plantings are exclusively Hass. “The demand, both locally and internationally, is far greater for Hass,” explains JAFF, “it is also easier to work with dark skin varieties.” He does add that, in SA, Fuertes are still very popular as well.

Lamb Hass and Reed have been planted specifically for the late, local market – JAFF has about 20 hectares of those. He says the Reed tastes nice but the seed/pip is large. “It’s not a popular variety,” he says, “but it still sells and gives us the best return, of all the varieties, back on farm, because of the timing.”

The remaining 30 hectares is made up of Pinkerton. “If I were to advise start up farmers, I’d suggest that they focus on Hass,” says JAFF.

Reed has an upright growing pattern.

Reeds are also quite distinctive in that the fruit stems are very short.

The distinctive round shape of the Reed makes it easy to identify. This one has extensive hail and insect damage – it will end up as either oil, guacamole or be bagged (which means it’ll go to local/bakkie sales).

So why is there so much Pinkerton on this farm, I wondered. “It’s a very high yielding tree,” shares JAFF, “and we expanded on the initial plantings because we felt there was still appetite for a green skin in Europe. That demand has subsequently changed, in favour of dark-skinned Hass.” The return per hectare, on Pinkerton, was higher back in the early 2000s, not because of the good price but because of the good yield. But now, with increased supply, it is harder to get the same returns because green skins are so easily damaged, ie: to get the good prices, you need to land ALL your fruit, in perfect condition, at the right time. “It’s just too easy to miss this window or for fruit to deteriorate,” says JAFF, “Hass is far more forgiving.”

JAFF says that input costs, on Pinkertons, are marginally higher than on Hass because they need one more copper spray, but it’s even higher on Fuertes which generally need between 5 and 7 sprays, because of increased cercospera and anthracnose. Pinkerton is less susceptible to these fungi. The Hass only requires one spray/year in this area.

Fully set Pinkerton tree with a healthy (30t/ha estimate) yield. Pinkertons are generally smaller trees. They tend to be narrower with a lighter green leaf.

I’m always trying to ‘guess the cultivar’ before JAFFs can tell me but I am really bad at my little game 😂🫢 JAFF says that Hass generally looks healthier and has more vigorous growth than a Pinkerton. Pinkerton’s stems (between fruit and branch) are longer than the Hass – Pinkerton below.

I’m always excited to come across new and different cultivars so when JAFF says he has the only commercial plantings of Cilfam, a South African bred variety, I was eager to meet her. He has a small block of this green skin variety and he sells the fruit on the local market. “It’s an Edranol selection that’s only real unique feature is a slightly rippled skin,” says JAFF as he shows me some of the fruit.

Cilfam fruit.

Cilfam.

Cilfam tree.

JAFF’s favourite avo, from a taste perspective, is Pinkerton but, from a farming perspective, it is definitely Hass “because it’s easy to farm and brings in the best returns” laughs JAFF.

Hass.

Lamb Hass.

LAND PREP AND RIDGING

This farm was developed on a tight budget so bulldozers and excavators were replaced by a big tractor and a plough. They deep ripped along the rows and built the ridges with the plough. As a result the ridges are not as high as JAFF would like.

Even if you’re able to afford specialized equipment, JAFF says he would be careful about getting too much subsoil above ground, “Maximise the height of the ridge without building it out of rock,” advises JAFF, “in other words, balance the size of your ridge with the quality of the content.”

Ideally, JAFF would aim for a 1m high ridge, made of top soil. When I visualized the height of this and my face turned into a question mark, JAFF explained that, from 1m, the ridge would settle a lot. JAFF prefers a wide ridge, rather than a mound, as this allows for broad root growth and optimal drainage. “Obviously everything about the ridge is dependent on soil structure,” says JAFF, “but I do believe they are beneficial and all avo farms should be developed with them.”

JAFF doesn’t rest ridges, unless there’s a pathogen threat to remove, because he believes they would compact when they settle.

Lime is applied as indicated by the soil samples and incorporated at ridging stage.

Ridges – JAFF likes them wide and gradual.

SPACING

The first orchards on this farm were planted at 6m x 3m which JAFF admits requires intense management but he’s happy with it. Any new developments are done using an 8m interrow though as it suits their tractors better. The distance between trees in the row depends on the variety: smaller trees, like Reed are planted between 3 & 3,5m. Hass, a larger tree, is planted at 5m intervals.

He would advise a new farmer to consider this standard size interrow, with variations in density within the row, when planning their orchards as it’s worked well internationally and for them.

ROOT STOCK

The older orchards are on Duke 7. Since those, Velvick, Bounty & Dusa have also come in. “Bounty seems to help keep the trees smaller (less vigorous),” says JAFF, “Dusa is more phytophthora-resistant.” Velvick and Bounty are Australian. Dusa is South African.

“Clonals are the only way to go,” advises JAFF, “Seedlings are too risky.”

PLANTING

As part of the research into crop farming, JAFF’s Dad visited Australia in 2000. There they tend to plant up and down the hills rather than along the contours as is more common in SA. The main reason is mechanization as tractors sometimes struggle with narrow, angled ledges and labour is used less extensively on that continent. JAFF Snr decided this made sense and adopted the same pattern on his farm. JAFF Jnr has maintained that, accommodating North-South aspect as much as possible. They still have a contour structure to manage water but this structure can be driven over by a tractor and spray rig.

JAFF plants up and down the slopes, rather than with the contours although, as can be seen in the distance, contours are still used to manage water flow.

JAFF adds, “Time of the year (for rain) is always very important when planting this way as erosion is a major concern.”

Irrigation is always prefitted so that the new trees can be watered immediately.

When it comes to the detail of getting the baby trees in the ground, JAFF marks the placement with wattle stakes. Planting starts as soon as the trees arrive from the supplying nursery. Some farmers prefer to acclimatize the trees in a small on-farm holding nursery but JAFF hasn’t found this necessary. So the trees are offloaded and moved into the field the following day. One team digs (JAFF never pre-digs holes because the walls of the hole can harden and compromise the growing roots), another team puts the tree in the hole and closes up. Because there is water right there, they don’t create a dam around each tree. “Please remember that avos do not like soil on their stems so it’s really important to cater for any subsidence that may happen post planting,” warns JAFF.

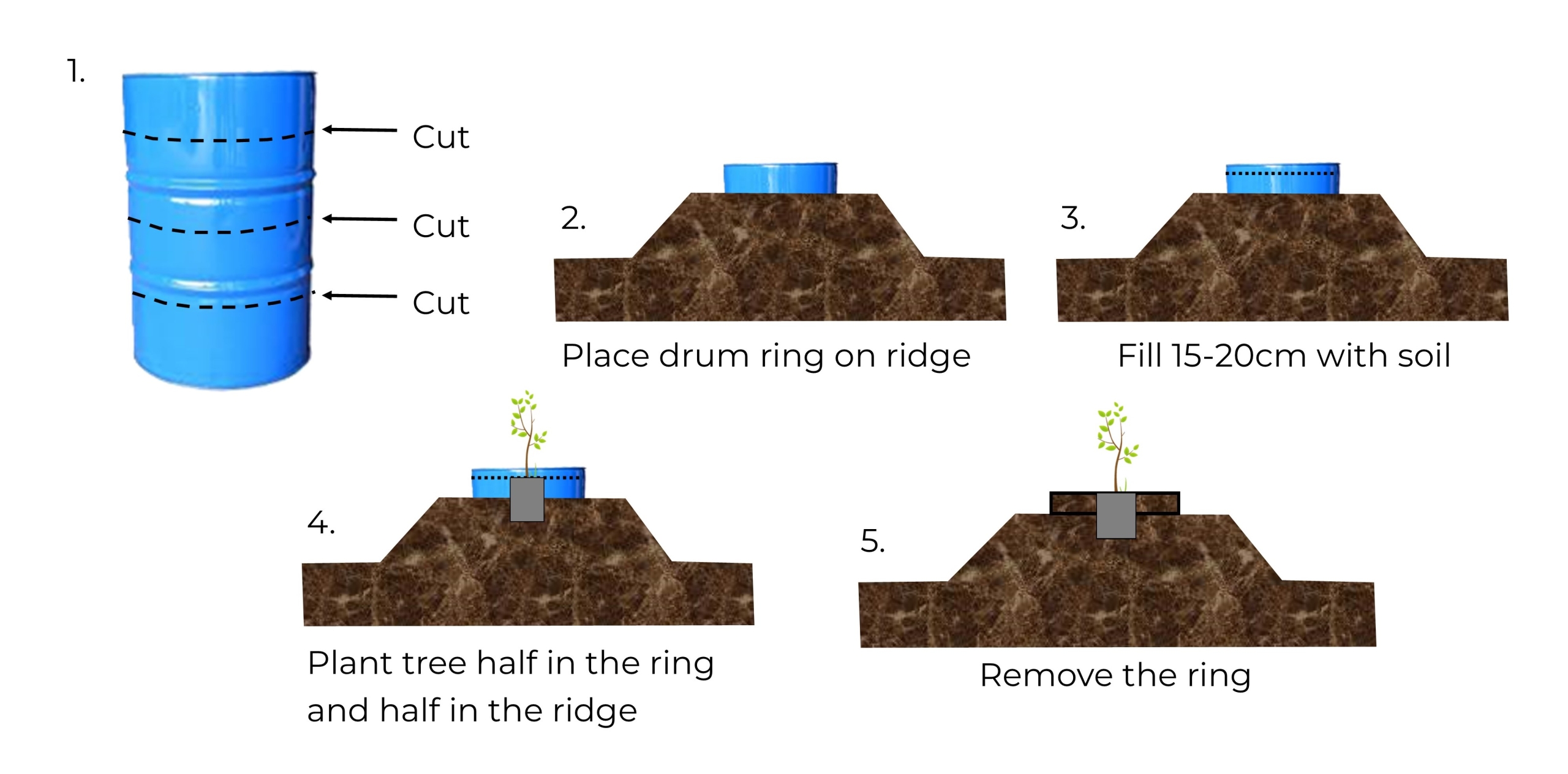

There are a number of ways to address this danger but JAFF uses 200 litre drums to frame some height on the ridge.

This technique is designed to avoid soil being able to wash on to the stem or a basin around the stem developing. Ie: both soil & water drainage is maximized.

JAFF doesn’t add anything in the hole with the new tree. He also doesn’t mulch around the base. About a month after planting, they add a fungicide to eradicate any harmful elements like phytophthora. At this stage they put down wood chips (preferably decomposed) or grass as a mulch. Herbicides are also sprayed to manage weeds.

STAKING & FENCING

The trees are staked, using the same wattle stick that marked the placement of the tree.

And then JAFF had a ‘fencing’ method that I’ve never seen before; he cuts ref-mesh sheets into 3 equal parts and rolls them into rings. These are painted and placed over the tree. Hot house plastic sheeting is then placed onto this structure, leaving a small gap around the base so that air can circulate in summer but herbivores can’t reach the tree. In winter, the plastic is folded down to close the gap which then keeps cold air out and works as frost protection. A protective micro-climate is created in the ring. These rings stay over the trees for about a year but they are reusable; with the plastic lasting for over 10 years!

We found this unused example lying in one of the orchards – JAFF said the plastic on this one is at least 10 years old. It’s so simple and easy – just slip it over the tree. Keeps browsers out and microclimate in.

IRRIGATION

“Don’t plant an avo tree unless the irrigation is there,” is JAFF’s caution here. Although they’ve considered low-flow drip to further improve results, they’re still happy using micro-irrigation.

I wondered why the avos had water and the macs didn’t, “The macs have an irrigation plan ready to go, as soon as they’ve proven themselves worth the investment,” assures JAFF. The water source on this farm is a stream that’s been dammed. “It’s proven to be both reliable and strong,” says JAFF, “but we all know how precious water is so low flow drip could be a solution if supply was ever threatened.”

The farm has a beautiful, long, narrow dam fed by a stream which has proven surprisingly reliable even through some epic droughts.

Micro-irrigation is the tool of choice on this farm.

MAINTENANCE OF VEGETATIVE GROWTH

JAFF prefers to keep vegetative growth in the interrow and to slash it rather than poison it so that erosion is controlled by the roots in the ground (remember their up-downhill rows)

Traditionally (although they want to reduce this) they’ve used glyphosate to kill interrow growth.

NUTRITION

A few weeks after planting, the trees get the first round of supplements in the form of a foliar feed containing the usual micros and macros. A few weeks after that they get a granular or powder fertilizer but JAFF warns that you have to be very cautious about over applying fertilisers as young trees can burn very easily.

Soil and leaf samples are taken every year, around April / May. Suppliers (fert & chem) use the results to make recommendations. JAFF also invites the extension officer from his exporter to weigh in with his advice. Between them all, they come up with a plan, based on recommendations as well as experience from previous years. “We don’t do a lot of reinventing the wheel though; we’ve built up a lot of knowledge and most of the lessons have been learnt; now it’s more a matter of topping up what’s short,” says JAFF, “and gut feel also plays a big part.”

All fertilizer is applied by hand, per tree. JAFF has trained his team to apply double fertiliser to any trees they see looking sick. They try to go in more often, with smaller amounts, rather than fewer times with larger amounts which results in continuous fertilizing especially during the growing season.

As mentioned in the intro, soil health and soil life is becoming more of a focus with the initial intervention being to add organic matter. The mac husks are decomposed and placed under the avos. (No question about who JAFFs favourites are) “Avos respond well to a healthy mulch,” defends JAFF.

Macadamia husks over the last 2-3 years, being placed under avo trees currently. They don’t add anything to these husks.

JAFF warns that, if you’re using sawdust as a compost/mulch, that it can easily compact and result in an impenetrable barrier that then closes off the soil below. JAFF advises, “Use it carefully and monitor it.”

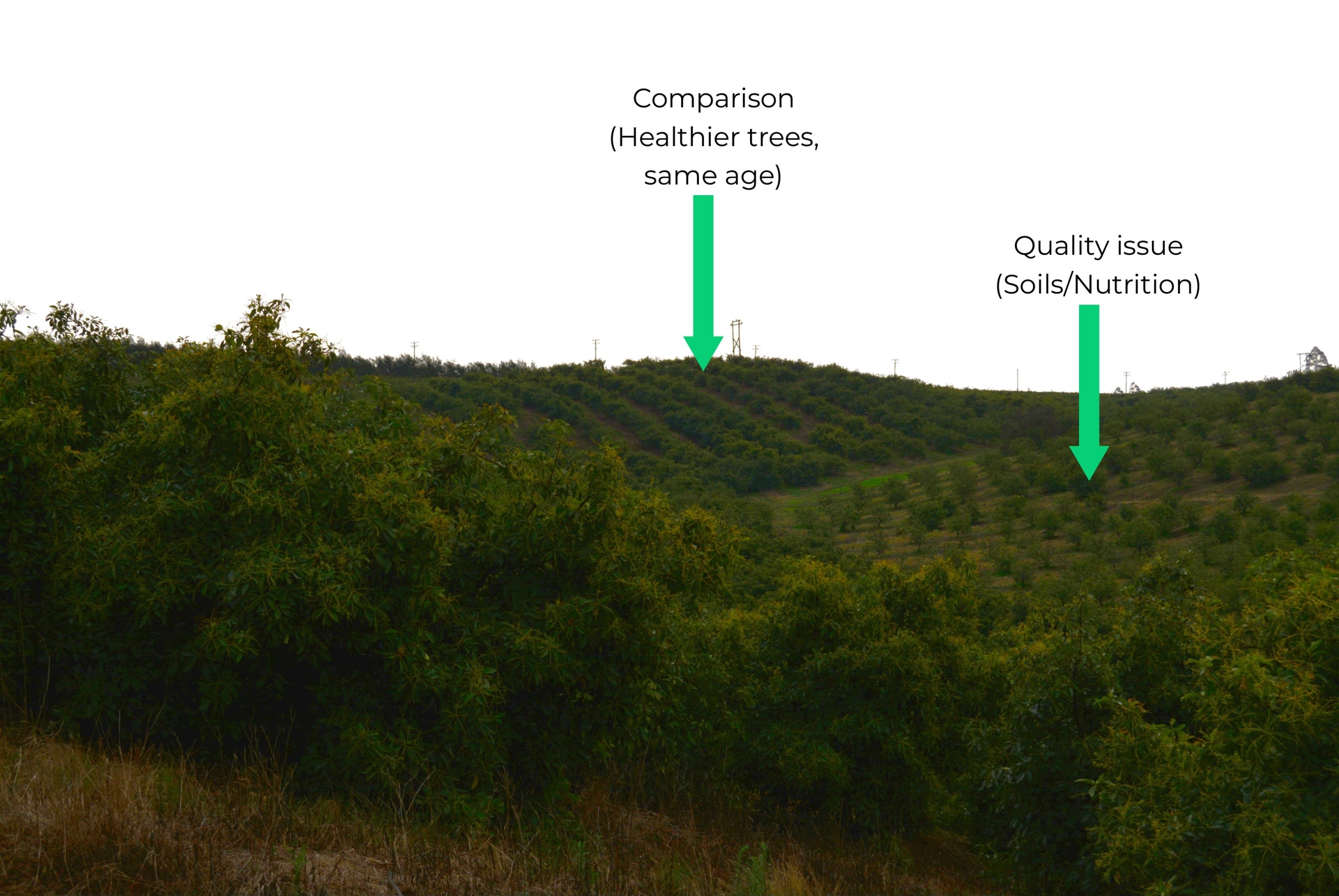

There is a ‘weak’ patch on the nearby hill (JAFF doesn’t know yet whether it is disease or nutrition or what it is) – trees above and below are fine, just an undefined weakness in the middle. They’ve applied mulch there already and have seen the feeder roots come up so he’s hoping for some recovery. There are a few south-facing, predominantly sandstone, slopes on the farm that look like this which makes him think it’s a nutrition (soil) issue. He’s going to address this by supplementing with better quality soil and organic matter in ridges. They may even chip wattle (which they farm), allow it to decompose for a bit, and apply that. Another possibility is to retro-ridge with an excavator.

Close up of some really weak trees. This was a trial planting for various root stocks; which may be why they’re in such awful condition. The soil quality here is also very poor and no ridging was done. So many possible reasons for the quality issues; JAFF will be redoing this orchard completely.

SOIL (& PHYTHOPHTORA)

JAFF says that soils with a high organic matter don’t dry out as quickly as those without organic matter.

Mulching.

The clay content across most of the farm is quite low, but there are a few pockets where it’s a concern as the phytophthora tends to be worse; in these areas they focus on controlling the phytophthora by injecting the trees with phosphonates, being mindful of MRLs (minimum residue levels) on export fruit. “What is the timeframe for this chemical to work its way out?” I asked JAFF. He admits that this is unclear so they try to inject with the first root flush of the season (Oct/Nov). The thought behind this is that the roots will use & retain most of the phosphorous rather than sending it up into the fruit. “Managing MRLs is very difficult,” explains JAFF, “I’ve seen MRL differences between fruit off the same tree. The limit is 50ppm. The best we can do is inject as early as possible and only when the trees are showing symptoms of infection.”

Rather than doing farm-wide, blanket injections, it’s an orchard-by-orchard assessment. But when an orchard is identified for treatment, all the trees in that orchard are injected – generally 2 injections per tree, with an extra 1 or 2 on trees that look sick.

CLIMATE

The cooler, more temperate climate means that this farm harvests about 1 month later than the rest of the industry. This lands fruit in Europe when supply is lower than the month before and, therefore, prices are better.

Being on the edge of a mistbelt, the rainfall is higher than average at about 1000ml annually.

Berg winds burn flowers (which increases flower drop) and scalds young fruit (which negatively impacts the pack out of export fruit).

Last year they had a really bad hail and couldn’t export anything as a result. The frequency of hailstorms has increased but they’ve noticed a trend over time that indicates a really bad one happens every 15 years. This was last year’s storm so, hopefully, the next 14 years are (major) hail-free!

The farm is insured for total wipe out only, not incidental damage.

Early damage from an unknown source. JAFF explains that it’s very hard to be certain about what has caused some damage; he says this might be heat or even a caterpillar.

Hail (light brown mark) & sun damage (dark mark lower down) – hazards of life on the outside!

Although this is a hilly farm, which can be challenging for mechanisation, JAFF says it is a good thing for frost as the cold air drains away down hills, into valleys where they avoid planting.

PEST MANAGEMENT

“Disease pressure, at this altitude, is far less than in more humid areas closer to sea level,” explains JAFF, “we’re also slightly isolated which further decreases the pressure.”

In fact, they haven’t needed to spray any pesticides or fungicides on the macs yet. This makes JAFF really reluctant to do that first spray because he knows how that will rock the ‘boat’ but he’s realistic in that it may still come to having to spray if the pests cause too much damage. Everyone has their own tolerance and JAFF is finding his tolerance is quite high; he’ll sacrifice a few % for the ecological balance he feels he has now.

To further aid his pest control, JAFF has kept a green belt between the two crops which he believes will minimise cross contamination if there is a ‘plague’.

Phytophthora remains the biggest problem in his avos. “Avos are not the preferred food of most insects,” says JAFF thankfully, “but if we do get some in, the green skins suffer more damage than dark skins.” Fruit flies are a bit of a concern and they use pheromone-baits and poison to control populations without damaging other insects. They have managed to avoid spraying pesticides for the last 2 seasons (in avos), “we did have some scale but managed it with a fruit oil which was added in with the copper spray.” JAFF explains that scale doesn’t actually damage anything, it just sticks onto the leaves and fruit, even through the washing and packing process, which affects pack out. Exported fruit cannot have live insects!!

POLLINATION & CROSS POLLINATION

There’s a strong bee presence on this farm as well as a number of wasps and other beneficials. JAFF has also brought in hives, over flowering season, for the macs but the avos are fine without this additional layer of insect activity.

Cross pollination is of more interest to JAFF in the macs because his research has revealed that almost every nut has cross cultivar heritage. To aid cross pollination, they’ve planted pure blocks but scattered these to make sure that the different cultivars are close to each other.

Hass flowers (in male phase) with some insect life.

PRUNING

The young trees are left to grow ‘wild’ until year 4 or 5. While this may sound quite old, JAFF reminds us that, because of the cooler climate, growth here is not as vigorous.

Pruning focuses on opening windows and alternating leaders with one to two serious cuts per tree per year and a follow up visit to manage regrowth. JAFF says macs and avos are similar in that they both require the development of lateral (rather than vertical) growth.

With the macs, he tries to manage a central leader with whorls off that. But the avo pruning is more about developing a champagne glass shape, with alternating leaders. Neither crop is skirted but JAFF says the macs tend to wear their skirts shorter while the avos prefer longer skirts that often brush the ground. He leaves them like this even if the fruit touches the ground. “I like to keep all growth as low as possible because this makes for easier spraying and other orchard management practices. I focus on encouraging production close to the centre, on both avos and macs.”

JAFF notes a few cultivar-specific pruning points:

- Hass – reacts more strongly to pruning in terms of regrowth which can be rampant near the cut site. This means that the follow up visit, to weed this out, is vital in Hass especially.

- Pinkerton is a bit slower and will have more uniform growth along the stem up to the cut site. JAFF says this still needs to be managed though.

Overall, JAFF advises that you don’t overcomplicate pruning and that you develop some on-farm, in-house pruning specialists.

Avo pruning shape – like a champagne glass.

YIELD

JAFF gets about 8-10t/ha average on avos across all orchards. Once all hectares are in full production, he hopes to get 12 t/ha. Pack out now is 40-50% with a goal of 70%. “That would result in a very viable operation,” dreams JAFF.

HARVEST

Harvesting starts at the end of June, with Pinkertons, and this continues through July.

Next is Hass, which they harvest when they’re holding 75/76% moisture. This usually happens from mid to end August through to October.

Finally it’s the Reed and Lamb Hass in November and December. They can even be harvested in January but JAFF says this is not ideal for the trees. “There’s a price to be paid in the following harvest if you hang fruit too late,” shares JAFF, “but can be done – it’s a tradeoff between maximizing revenue this season or next.” (Avos tend to bear alternately – have a good crop one season followed by a poor crop the next – if the fruit is hung too late)

In terms of the harvesting job, JAFF said, this too, should be kept simple; “the guys climb and pick.” They use sticks if they have to but don’t need ladders because the trees are kept small. Each picker has a bag, and they break avos off the tree by hand. Bags are weighed before being offloaded into a large bin. Stems are snipped with secateurs in this process. Once the picker reaches a preset volume, they are incentivized by getting a higher rate per kg for all kgs picked by them that day.

There are 4 big bins per trailer. From the trailer the bins move to a truck that delivers to the packhouse.

INSIGHTS

JAFF says, for him, the hardest part of avo farming is the price. Practices are something you can refine and learn from previous experience but prices! – they are less predictable. The fluctuating prices also dictate your next season; if they were low, your cashflow is less and you have less options (in terms of fertilisers etc) in the following season.

“Oh wait – hail is actually the hardest part,” JAFF grimaces, “Working with things outside your control makes you realise how insignificant you are.” JAFF says he thinks farmers are the biggest gamblers and he has no idea how people, without faith, farm; “that must be so hard because then it’s without reason,” he muses.

JAFF says that, apart from being faith-filled, farmers need to be all-rounders and good students, “Never let your pride trip you up; continuously learn and be willing to listen and ask questions of everyone around you.” JAFF focuses on this with his children; by making sure he always answers their questions properly and encourages them to learn from everyone around them.

This beautiful old Hass orchard had a healthy canopy which created a cool, quiet space underneath. The age and strength of this orchard was palpable.

And here we said goodbye to yet another incredible JAFF. Thank you for sharing your time, experience and expertise – we are all grateful!!